Clare Bowditch: Putting Hope Into The World

This podcast is patron-funded and ad-free! Please support us on patreon for as little as $1. For a post about this entire podcast (stories, photos, links, reading list, transcript and more) go to: https://www.patreon.com/posts/47078444

books, bereavement and breaking down.

Reading is an empathy factory. When I read Australian singer-songwriter Clare Bowditch’s memoir, “Your Own Kind of Girl”, I related deeply to her struggles with insecurity, self-worth and sanity. We had so much in common it was uncanny, like finding an accidental lost twin sibling through a bookshop. Join us as we talk (and laugh, and cry) about owning your own self-doubt and self-hatred, how books can actually change your life, the emotional cost of telling your own true story….and more.

Episode 20 of The Art of Asking Everything: Clare Bowditch: Putting Hope Into The World is out now wherever you get your podcasts.

Here’s a link to all the places you can get and subscribe to the podcast: https://linktr.ee/AskingEverything

Show notes:

Description

Amanda Palmer presents an intimate conversation with Clare Bowditch, recorded March 6, 2020, at Sing Sing Studios, Melbourne, Australia.

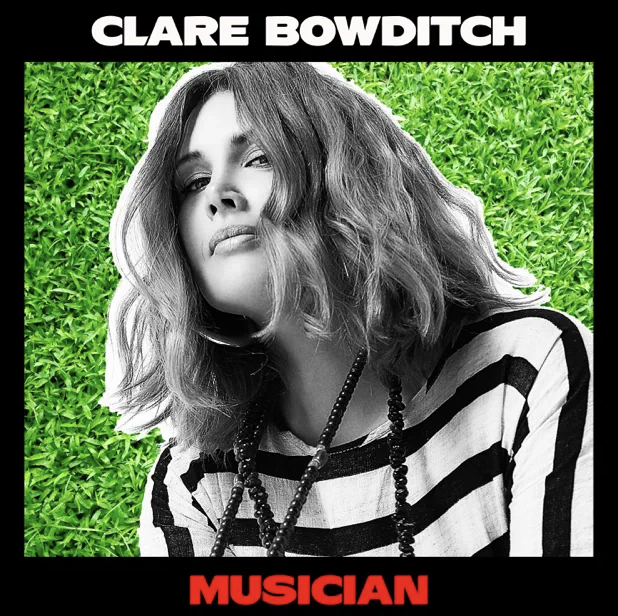

Clare Bowditch is an Australian actor, radio presenter, and entrepreneur.

She started performing in the Melbourne pub circuit at seventeen years old.

In 1998, she formed the band Red Raku and recorded two albums along with producer and drummer Marty Brown—who is now her husband, producer and music manager.

In 2010, Clare was awarded Rolling Stone’s Woman of the Year.

In 2006 she won the ARIA Award for Best Female Artist and in 2012 was nominated for a Logie Award for her work on the TV series Offspring.

She has since founded Big Hearted Business, a training ground and classroom for other female entrepreneurs.

Her memoir, Your Own Kind of Girl, is an exploration into her own inner critic that pulls no punches. If you’re an artist, you’re going to want to read this book.

She also hosts Tame Your Inner Critic – an Audible Original that’s a playful take on self-development.

CREDITS:

This has been the Art of Asking Everything Podcast.

Thanks to my guest Clare Bowditch, check out her music, book, and other things at clarebowditch.com

Our interview was recorded by Nick Edin at Sing Sing Studios in Melbourne, Australia.

For all the music you heard in this episode, you can go to the new, improved amandapalmer.net/podcast.

This podcast was produced by FannieCo.

Lots of thanks, as usual, to my amazing team. Hayley Rosenblum, Michael McComiskey, Alex Knight, Jordan Verzar, and introducing Kelly Welles, who’s been helping me newly on the social medias.

And last but not least, this whole podcast would not be possible without patronage. Like I said at the beginning, this keeps us ad-free, sponsor-free, endorsement-free, weird-corporate-podcast-world-

And special thanks to my high level patrons: Simon Oliver, St. Alexander, Birdie Black, Ruth Ann Harnisch, Leela Cosgrove, Robert W. Perkins. Thank you, all of you, whether you’re in for a dollar, or more, for helping me make this podcast.

Things are going to evolve over the next couple of weeks and months, so stick around, and see what happens, I’ve got some really exciting guests coming up in the next while. So, so, so excited!

Thank you.

Signing off, this is Amanda Palmer. Keep on asking everything.

This podcast is 100% fan supported. There are no corporate sponsors or restrictions on speech.

No ads.

No sponsors.

No censorship.

We are the media.

Exclusive content is available to Patrons only.

Go to Patreon.

Become a member.

Get extra stuff.

Join the community at patreon.com/amandapalmer

FULL EPISODE TRANSCRIPT:

Amanda 00:35

This is The Art of Asking Everything. I am Amanda Palmer.

Before we start this episode, just a note about the podcast itself. We are slowly coming to the end of what we’ve been calling the ‘historical’ recordings. When I was on tour last year through 2019, I interviewed over 20 people, and we’ve been putting these podcasts out every week with the Patreon basically funding the whole production. And that is about to change. Not the patronage, but the historical part, because we’re caught up. And the exciting thing now that we’re done putting out all of these historical recordings, is that I can work in real time. So starting next month, I’ll be interviewing real life people, right now, right here. These interviews won’t be from a year ago. And the frequency of the podcast might decrease a little bit while we get the production value up, and while I get my footing, and we’ll see what happens, we’re experimenting.

But meanwhile, a reminder that the reason this podcast has no advertisement breaks, and no sponsors, and no ‘you can hear my podcast now exclusively on Spotify, or Luminary, or fill in the blank!’, the reason I have no overarching superiors telling me what to do with my podcast, is because of Patreon. So I am coming to you to ask you to join the Patreon, it’s a dollar, it’s an amazing community, it’s awesome, it pays my staff, it pays for the production, it pays the podcast guests, it makes all of this possible. So please join, even if it’s just for a dollar a month, it would mean the world to me and my team, and it will keep us corporate free. So if you’ve been listening and loving, please, I am talking to you, put your money where your ears is, and I thank you. And to all of my Patreon people who have been supporting for the last, going on six years, you know how much you mean to me, thank you so much for making my whole life, and all of this, possible.

This week’s guest is Australian singer-songwriter and memoirist Clare Bowditch. I met Clare sort of through the indie music scene in Melbourne a few years ago, and we didn’t really know each other that well, but this past tour, when I was in Australia around December 2019, and this was just before the bushfires and COVID all sort of wiped out our ordinary lives, I ran into Clare’s new book, in a little book store on Brunswick Street in Melbourne. And the cover was what grabbed me, and I recognised Clare’s name, and I didn’t know she’d written a book. But there was this photo of this little girl in a swimsuit. And this little girl kind of looked like, 8 years old, but also 67, as if she should be holding a pack of Pall Mall cigarettes and a dry martini. She was wearing these designer sunglasses, and looking really, really real for an 8 year old. And I thought, Clare, I’ve got to get this book, so I bought it, and I read it.

And then, because Clare poured out her story, and her truth, and her pain, onto the page, and she goes deep, her eating disorder, her insecurities, her full mental breakdown, her sister’s death… I read this book, and I knew her. I knew, now, who this person was. And we had so much in common, and I was so glad to know her. And I knew she lived in Melbourne, and I wanted to be her friend, and just as I had bought the book, I ran into her, not literally, but there she was in the street, and I was in the street, and she recognised me, and it all felt really fateful. So I asked her to come on the podcast to talk about the book, but also about music, and life, and everything.

And as a person who’s written a really honest memoir, I also like feeling the other side of this sort of strange recognition. Because when someone has read The Art of Asking sometimes, my memoir, they will come up to me and say, ‘Hey, Amanda Palmer, it’s very silly, but I feel like I know you.’ And I always say that it’s not silly. You do know me. Because I told you who I was, in my book. You do know me.

And that being said, there’s a lot that you can’t tell someone in a memoir, because it’s not fair, or safe, or kind, to the people in your life. And as I was reading Clare’s book, that’s what I kept thinking about. It was like, what did she have to leave out? How did she ride this line? How did she tell this story without hurting her family? And that’s what I found myself wanting to interview her about. How do you tell the truth in a book without hurting people? Or in a song, without hurting people? And I know what I had to do, for The Art of Asking. And I wanted to know what she had to do in her book, to ride that line of truth and compassion.

Also, sidenote, because of getting to know her through her book, I also invited Clare to duet on a track with me for my Bushfire benefit album, which I round up calling Forty-Five Degrees. And it’s the song you’re listening to right now.

Here we go. And whether it is the books we both read, or the little acts of kindness from strangers that saved us both in our darkest moments, or the emotional cost of telling our stories, this is it. The overarching theme of this episode… What are the mechanisms we develop to cope with the shit that life throws at us? She’s really good at it. Meet your new friend, Clare Bowditch.

Amanda Palmer 07:04

Clare Bowditch. Hi.

Clare 07:06

Darling. Amanda Palmer. Gosh, it’s beautiful to be here with you.

Amanda 07:11

Talk to me about Frank.

Claire 07:13

Frank. Now, I wanna front-load this with an apology to anyone who is called Frank.

Amanda 07:19

Go for it.

Claire 07:20

But I’m quite tender about Frank these days. Frank is a name that I gave at the age of 22, 23, I spontaneously gave to the voice in my head that I identify as my inner critic. People in history have called it our ego, our saboteur, the id, the devil. For me, it was really useful to name the clusterfuck of feelings I was feeling, to name it Frank. And Frank was just the name of someone, I didn’t know anyone called Frank at the time, and it was off the book of reading a Jack Kornfield book, A Path With Heart. Now, are you familiar with Jack?

Amanda 07:55

Oh my God, yes. So, if you don’t know who Jack Kornfield is, he’s one of the…

Clare 08:01

Run, don’t walk.

Amanda 08:02

One of the most old school American mindfulness, vipassana meditation teachers, writers. Think old school, 70s, brought meditation to a lot of people in the Western world.

Clare 08:18

And he has a wonderful, playful sense of writing, and voice in writing, and this great sense of humour.

Amanda 08:23

So you were reading Jack Kornfield when you were 22?

Claire 08:26

Yeah, oh yeah, I was reading anything I could get my hands on.

Amanda 08:29

How did those books come into your life, how did you know about them?

Clare 08:31

I was desperately yearning to find this sense of an other, of a higher power, of a God, of a way of thinking, of a way of living, of a way of staying alive, of a way of finding meaning. So I guess I was on that journey young. I was brought up in a deeply religious, very profoundly faith-driven family. We were brought up Catholic, my mum was Dutch, her faith was profound, my father’s faith was profound, and I knew I didn’t fit neatly into Catholicism, but I saw the gift that they had, and this focus on love. So I got that bit, but I was deeply rebellious, and I guess I started reading A Course In Miracles when I was about 16, and I had no idea what it was about. I probably came to it via most people, I watched Oprah as a 10 year old.

Amanda 09:21

Really, no, but that’s important, how books wind up in our lives. I don’t think it’s unimportant how these books find their way to us. Because it could just be there was a good book store with a curated section and it was lying on the table, or an older friend goes, ‘I think you might be interested in this and need to read it.’ And when I think about some of the books that changed my life right around that age, I look back and I don’t take for granted that the books that opened up my head canon didn’t wind up randomly in my lap, they came to me.

Clare 09:52

Tell me one.

Amanda 09:54

I had a book that really changed everything for me, right around the same age, I was about 25, and I read a book called Dropping Ashes On The Buddha, by Seung Sahn, who was a Korean Zen master, given to me by my mentor, Anthony. I’d had it kicking around for a couple of years, and I was travelling in Australia for the first time, I was a street performer, and I just decided to give it a go one day. It was the book that I needed at the time that I needed it, about non-attachment, and mindfulness, and Frank, and the voice in your head that is controlling you, and you’re just not really noticing it, because you’re just lost in it.

So when you were in your teens or your early 20s, what was Frank saying?

Clare 10:36

So for me, Frank had actually been with me from a very young age, and again, we speak about it playfully as the voice of another, as a way of detaching or having some distance from that cruel voice in our head, which I know now is a very normal, natural function of a survival brain, it’s part of our ego, a part of our drive, it’s completely entangled in everything wonderful that I’ve ever been driven to do as well.

But it was, for me, very loud as a kid. Not long after and around the time of 5, when my sister passed away, my sister Rowena was 7, I became very aware then of this voice of wrongness within me. And children are complex in the way that we process trauma. For me, for whatever reason, I was the fat kid in my family, I was the fat kid at my school. I was much taller and much bigger, and I always had been. And Frank developed as a ‘there’s something wrong with you’ sort of a voice, it was very loud in my head. I was bad. I didn’t have any language for my sadness, or where to put my grief. And then as a teen, it really focused strongly around my body, around my role as a woman in the world, around wanting to please my parents.

But at the age of 21, it had gotten so incredibly loud, I was actually travelling, and trying to find my life, adventure, you know, I knew I wanted to do something with my life, but I somehow ended up working at a call centre and dropping out of uni, and really not feeling confident enough in my body size, in my voice, in my heart, to step into showing the world who I was. And the voice then got so loud that it was really dangerous. That was around the time that I had my toughest, toughest time with mental ill health, which probably one of our listeners will know about, because this is such a common experience. But the reason I talk about it is because it’s the most useful experience of my life, and the story of my recovery is a story that so many people share.

Amanda 12:40

So one of the things that I felt reading your book, which is incredible, by the way…

Clare 12:45

You are.

Amanda 12:46

Was just a sense of ‘twinny-ness’. Because I went through a really similar kind of confounded breakdown around the same time in my life, and I was abroad.

Clare 12:59

But did you know what was going on?

Amanda 13:01

No. When I was 19, and I talk about this in my show, when I was 19 I lost a boyfriend that I had just broken up with, died over Christmas, and I had broken up with him, mostly because he had a hard drug habit and I didn’t know how to handle it. And then right after that my grandmother died, and then my grandfather died, and then my older brother died.

Clare 13:21

Good lord.

Amanda 13:21

All in about six months. Right as that happened, I went abroad to study in Germany for a year, and I had access to alcohol for the first time. Like you, when you left Australia and went to London, it’s the nadir, or the peak of the book, whichever way you wanna look at it, you leave your safe little community in Melbourne and you go off to the UK, hoping to find yourself and have your adventure. And I went off to Germany to study, hoping to get away from everything and find myself, and find my adventure, and instead I just became an insane person, and a drunk, who was just careening around and fucking everybody, and pretty much getting sloshed every single night. And also on anti-depressants, and also just clueless. I had a complete existential collapse breakdown that year, and no safety net.

I just wanna zero in on this one teeny little detail in the book. You’re in London, or Oxford, I can’t remember. You’re on the edge of a kind of suicidal depression, and you don’t know what’s going on. And you don’t really have any family there, and you don’t really have much community. And there are these teeny little acts of kindness. These people that you barely know look at you. They don’t really know you, they don’t really know what you’re going through, they don’t really know what’s going on, and they just take care of you. And I remember…

Clare 15:02

I can’t even think about it without tearing up, still.

Amanda 15:06

Yeah, and you can tell a couple of those stories, because I feel like they’re so important.

Clare 15:10

Oh, they’re so important, they were life-saving.

Amanda 15:12

I remember being about that age, again having no idea what I was doing, and I wanted to go to this performance art workshop in California, I didn’t know anything, I didn’t know anyone, I saved up my money, I bought a plane ticket, I landed in San Francisco, I stayed at a really, really shitty little youth hostel, cos I could only afford $13 a night. And the minute I got there, and the first day of the workshop was supposed to start, I got incredibly ill. I got the kind of flu where you can’t get out of bed. And it was before cell phones, and I had no one I could call, and I was just deathly ill, on the bottom bunk of a shitty youth hostel, paralytic, just going, ‘I don’t even know what to do!’

Clare 15:57

I’m shivering thinking about it, you poor darling.

Amanda 15:58

I don’t know who to ask, I’m shivering, I’m sick. And this random guy who worked the front desk one shift at the youth hostel sort of clocked what was going on. And I was just this weird-looking 24 year old kid or whatever. And he just was like, ‘I’m gonna take care of you. You’re gonna be okay. What do you need? I’m gonna go down the street and I’m gonna get you some food. I’m gonna get you some soup.’ And I just remember being also so clueless at the time that I was like, ‘Why are you being so nice to me?! I don’t understand what’s going on! Why are you being kind?!’

But all of these, there were so many moments like that in my life in Germany too, where I think back at these acts of gorgeous, unnecessary kindness that these total strangers, especially when I was drunk, and I was lost, and I was in danger, and I had put myself in these stupid ass positions…

Clare 16:54

Cos it connects you to this sense of something much bigger. You were so vulnerable, and then that kindness comes in, and it just makes you feel like you are part of something good. And I think in those moments, and I’ve seen this in everything you do, your resolve is then to wanna pass it back along. Once you know that kind of kindness, and we are lucky as humans that many of us will understand that kindness at a certain point, you just don’t forget it, because it’s gotten into you deeply, and it changes everything.

Amanda 17:29

Absolutely. Can you tell one of those stories?

Clare 17:32

Yes. I just wanna say, you couldn’t see this, dear listener, but as Amanda was telling that story, her eyes were full of tears, and mine were too, just thinking about this. Because the people who were kind to me I never even saw again, but I still carry them with me. So I was in London, I had gone on my grand adventure, I’d also had a devastating break-up that I didn’t want to break up, did break up, just one of those motherfuckers of a break-up, and off I went to London, completely unprepared, with very little money in my bank account. And I was lucky to have a dear friend, Libby, who was there, one of my best friends to this very day, who was there in London.

To set the scene, I stopped being able to sleep, we’d had an experience on a train with a friend who’d fainted, and it had triggered in me post-traumatic stress disorder, which I didn’t know I had, I had no idea. Just for me, that meant recurring flashbacks, nightmares, and waking up through the night, and being unable to leep, and it spiralled. So I started being very sensitive to noise, and very sensitive to all sorts of things. I’d decide that I’d wake up, a grand idea, I’m gonna go to Oxford and have some quiet time, and perhaps find, I don’t know, my gang, my people, I didn’t know what it was.

Amanda 18:48

And how far is Oxford from London? It’s pretty close, right?

Clare 18:51

Yeah, it was a couple of hours on the bus. I caught a bus there. This was now 23 years ago, so I remember that journey, I remember feeling an immediate sense of relief. The city of Oxford, something about it soothed me, and I thought, good.

Amanda 19:05

Cute.

Clare 19:06

So gorgeous. I love the gargoyles, and the water. Anyway, I checked into the cheapest hotel – sorry, hostel, that I could find. And some wonderful things happened. Even though I wasn’t sleeping, I was in a room with probably a really big gang of other women. It was very noisy through the night. I didn’t realise at this point that I had stopped eating, and that I was just feeling sick all the time. And I had no context that this was actually cortisol, adrenaline, my life catching up with me. And it spiralled.

And there were two kind things that I really remember clearly. There were many, but there was one, a chap called Ian, which is my dad’s name, so I remembered his name, he was behind the counter. And I just thought, I’m dying. I had that thought in my head, that was one of my recurring fearful thoughts. I’m dying, there’s a terrible something happening to me, I don’t know what it is, I’ve clearly got a virus or something.

Anyway, he was kind to me, and he gave me a quiet room to sleep in, and just to be able to get six hours of uninterrupted sleep when he snuck me into a private room, and he called a doctor, and he helped me, and that kindness got into my bones. And I still remember his face, and I never saw him again. I did not get a chance to say thank you, because I grew so unwell from that point that I had to, Libby got me on a plane home, basically.

But there was another chap who I still remember to this day. He ran the local open mic. It was just in its infancy. It was called the Cat Weasel Club. And when I’d arrived at the backpackers, a lady had seen that I had a guitar, and I did that thing that we sometimes do in life which is a bit magical, where I wasn’t out yet as a singer/songwriter, but I desperately wanted to be out.

Amanda 20:50

But you were carrying a guitar around.

Clare 20:51

I was carrying a guitar. My hope was in that guitar, and I had three chords and the truth, and I’d written a couple of side songs. So off we went, she said there’s an open mic, and I had my first profound experience of having the courage to say yes to play on stage. And this guy, Tom, had said, you did great, that was great, invited me back in again, but I lost my confidence after that, and I didn’t go back in.

But when things got really bad, I remember getting myself into a church at a certain point, and feeling the darkest feeling that you have, where you can’t stop thinking of death, and for me I was very overtired, and I was very traumatised, and I didn’t want to die, but I couldn’t seem to stop thinking of darkness, really, and that there was no way out. And I remember walking out of that church, and sitting on a chair, and just weeping on the street of Oxford. And then past walked Tom. And he just said, are you okay? And I said, I don’t think I am. And it was so sweet, he said, right. You need a cup of tea. So we went to a tea room.

Amanda 22:01

So British. So British!

Clare 22:04

We got a cup of tea, and then he invited me over, he had a beautiful little barge.

Amanda 22:09

Like a longboat.

Clare 22:10

Yeah, a longboat. And he invited me for a home-cooked meal, and it was a real moment of light, where I had that hopeful feeling again. I didn’t realise it was my thoughts and my fear that was spiralling me back into the panic attack of the time. But that was my first clue, because I remember feeling safe with him, and eating a meal with him, and for a moment remembering my stronger self.

And then on the way home, my fearful thoughts came back in again, and I was back in Australia before I knew it.

MUSIC BREAK – Are You Ready Yet?

Amanda 23:19

This moment in the UK where your friend passed out on this train, and you describe it really beautifully, it just spirals you into PTSD panic that you can’t really identify at the time.

A lot of the beginning of the book is about two things: your basic scene growing up, and your relationship with yourself, but you talk a lot about Rowena, your sister, who you lost. You say at the beginning of the book, I knew I was gonna write this book. You had it in you as a directive somewhere from early on, I’m gonna tell this story, I’m gonna write this story down, and that that was a thought in your head all along. Did you have to be ready to talk about Rowena? And then why did you choose the moment that you chose to tell the story, which is such a hard story to tell?

Clare 24:11

For anyone who doesn’t know me, I spent most of my life here in Australia as a singer/songwriter, working in radio. These are not really stories that I spoke about in any detail, ever. And then I sat in my career, sort of spent 15 years in the public eye, and I’ve alluded to it, and I’ve written songs that allude to it, but I haven’t gone into detail because I have always known I would tell this story.

So when I was 21, I came home, 22, I had the good fortune to read a book, a simple little book by a woman called Dr. Claire Weekes, who was a stalwart of the Australian GP society, the first Australian woman to earn a doctorate at the Sydney University, she was quite a trailblazer, she was a GP who treated people with PTSD before there was a name for PTSD, and she did that using a simple technique, which I’ll explain to you in a sec.

So a friend of my mum’s gave me a book. She saw where I was at, I didn’t know what was going on with me, I just thought I was going nuts, and I’d lost a lot of weight, and I was finding it hard to leave the house or have any conversation or sleep, or just think of a future. And this little book came on my lap, called Self Help For Your Nerves.

Amanda 25:18

Nerves!

Clare 25:20

The kind of title that I might have dismissed. It had a little picture of a woman on the front who looked a lot like the queen, and I was that desperate, I needed something simple and effective, so I read this, and I learned about my nervous system, I learned about facing, accepting, floating, and letting time pass, and this is a technique for getting through what she called nervous suffering. And she had a voice like this, this is Dr. Claire Weekes speaking. I’m here to tell you that if you’d like to recover from your nervous symptoms, you can! So look up on YouTube, her voice is much cooler than that, but she was derided, she was seen as a mad woman, this psychiatrist said, ‘Who do you think you are, speaking in this space?’ But meanwhile, her technique helped me, it saved my life. It gave me a sense of being able to see into a future, and it gave me a sense of realising, ah, it’s my thoughts that are triggering these symptoms of panic, so I have some control here.

And again, in that moment of vulnerability, the gratitude came in. And I’d always known I’d write something, but I realised, ah, so this is the story that I need to tell, there is hope. And I said, I will write this story one day, and it made me feel enormously useful, and like life was worth living, to think that I might have something good to pass on down the line.

So I’m a kid here. I go to art school, I try writing it a few times, it’s too frightening, too terrifying. I avoid it. But I need the hope of the promise, and I wanna fulfill it, so I say, okay, I won’t write this right now, this book, cos I’m still in the process, but when I’m really fucking old, so 40, I will write this. Just really rude. So 40 came recently. And I thought, okay, it’s time to fulfill that promise, so it’s kind of that simple in a way.

But Rowena, speaking about Rowena, our darling Rowena… Look, I think I only really learnt to talk about her through writing this book, and through the conversations that I was able to have with my family. So my sister was a normal healthy girl, two years older than me, I’m the youngest of five, we’re all 18 months apart. As mum would say, decades on a rosary. Beautifully timed, one of the few successes of the rhythm method in history.

And there we were, a pretty normal, healthy, happy family, with all of our foibles. And Rowena got mysteriously sick when she was in prep. I was 3, she was 5. We had a really incredible community around us, but the thing that you don’t want to happen the most in life did happen, and Rowena’s illness was undiagnosable, and by the time they found a name for it, it was too late, she was already in the children’s hospital. So it’s difficult to talk about these stories often, because they’re shared stories, and our family’s way of really living through that experience of two years on life support in the children’s hospital, that was our life. So Rowie still has this record for the longest ever living child in intensive care in the children’s, because these days you might have a respirator that you can go home with or so on, but…

So learning to speak and understand it’s okay for me to have had a childhood experience, it’s okay for me to speak about the human rather than the faith-based context that my parents very cleverly gave us. Again, it’s a hopeful story to learn to live with it. And not wanting to speak on behalf of any of my siblings, cos each of us have had such different experiences. But I needed to talk about that, because that, for me, was the genesis of my illness later, and also the genesis of everything that I do in my life. My love for my sister, my family, is my driver.

Amanda 29:00

Those stories about Rowena, you don’t put her on a pedestal, you draw this really human portrait of the kind of person she was.

Clare 29:10

Yeah.

Amanda 29:11

And then all of these scenes in the hospital, and you’re thinking like a child thinks, because you just are given the reality that you’re given. There you are, going to the hospital again, spending all of this time by her bedside, doing what a kid would do, and thinking the things that a kid thinks about jealousy, and anger, and why does she get that, and why don’t I get that? And the older you get, the more you go back, and you look at those formative experiences, and it can be frightening to look at it, especially if you’re lifting up the lid on something new, and you’re like, oh my God, of course, this all makes perfect sense, 40 years later, how did I not know?

Clare 29:51

Well you and I, and most artists, know something now that I didn’t know as a kid, and we didn’t know as kids, which is that when we can tell the truth, the whole truth, as much of the truth as we can gather, when we can find a way to tell that, and be of an age or a maturity where we’re able to do that, that is pretty much it. That is the gift that we are passing on, and we’re trying to do that as beautifully as we can, or as truthfully as we can. That’s the gift. To feel that I’ve been able to say these things I was so ashamed of for all of my life, I was so ashamed of all the feelings I had about… I used to wish I could break a leg, so I could get to be in the hospital. And as I became a mother, earlier, the horror of really what had gone on became clearer and clearer. And then later also, what happened was the beauty of what had happened. My sister lived her full gestalt. That was her life. And that was a full, profound, glorious life, and she was just a normal little girl, and she was also a precious little girl. So to come to terms with that, and be able to speak that as an adult, I felt that was something I wanted to do to honour her.

Amanda 31:35

Especially as a parent, trying to imagine what your parents go through when they lose a child is kind of unimaginable. Of course your head goes there all the time, and your anxiety takes you there all the time, but I kind of try to imagine what would happen if Ash got hit by a car, and was just disappeared from the Earth. And it almost, probably for really important, protective sanity reasons, I can’t go there. I think I can maybe, but I feel like really I can’t.

And when I imagine what my parents went through losing my older stepbrother, and also the complications of, well, he wasn’t my real brother, he was my stepbrother, and he wasn’t my mom’s ‘real’ son, even though she helped raise him, and there was that extra layer of, I don’t even know how to tell this story, I don’t even know if I’m allowed to tell this story. The more I think about it, Karl was, I think he was 27, I was 20 when he died, and I think of the impact that it had on my parents, and what they did or didn’t deal with, even now. It’s almost so unimaginable that you can’t talk about it, and you can’t write about it, because what do you say?

And I watch you trying to tell this story, and we had dinner together the other night, and we were talking about this. Any time I read somebody else’s story in a memoir, I become more and more conscious of who you have to protect. What you’re not really allowed to say, and the stories that you can tell, you’re just skirting around. There’s a huge truth here, but I can’t really, totally tell it, cos I have to be really responsible to all these other people in my family, so how do I do it? How did you navigate that in this book?

Claire 33:36

Oh, it took a long time. First, it’s just understanding that it’s okay that I had an experience. The survival instinct is so strong, and so amazing in human beings. The things that we go through, and then keep chugging on, keep surviving. One of those experiences that was so normal to me, losing a sister, that I think I had these flashes, as a child, of how, cos it was a water that I’d swum in, I remember saying to my mum when I was about 11, just casually, off the cuff, we were in the laundry, and I said something like, oh, I’ll probably lose a child, too. And I saw her face, and her face was… And I just burst into tears, I said I’m so sorry, and she said, I think what came out of her mouth was, ‘Don’t say that!’ And I got that insight into, right, so this is…

Amanda 34:33

Not normal.

Clare 34:34

Not normal. This is not something that we want to happen. So a lot of what I had to understand was my brain was formed in this experience of trauma, and deep, deep love, and what really helped was my parents had to impose some structure. And for me, the routine of food, of meals, became really important, and the taste of meals, and the memories attached too. I knew I must never forget these times, so I have a very long, distinct sense of memory, because something in me knew, we must not forget. But then when it comes to being an adult, and trying to make sense of that, I needed to speak to my siblings, I needed to ask my mother questions that I had avoided asking most of my life, because who we love… Rowie’s in every photo on all of our walls, and is such a big part of our lives, but we’ve gotten on with living, and it’s difficult to say, hey, can we stop for a minute, can we go back there? So it’s a big ask. And I’m very lucky…

Amanda 35:38

Yeah, and just because you’re in the mood doesn’t mean anybody else is in the mood.

Clare 35:43

Exactly. You feel emotional as I’m saying this, what are you thinking of?

Amanda 35:46

I’m mostly just so grateful that you just kept being brave, and you pushed through, and you did it anyway. It’s such a gift, and I think this is the thing about being an artist who chooses to share a story, I’m not sure people are aware, and maybe they shouldn’t be aware, of what it costs to tell a story. The hidden tax of telling a story. Because by necessity, when you write a book like this, you have to make it look like a walk in the park, and no one is allowed to know the battlefield of landmines that you have to weave around to keep your relationship safe, to keep your community safe, to protect your parents, to whatever.

And I’ve been dealing with this in my show right now. I’m so proud of my show. I’m so proud of it, and I think it’s so good, and it protects everybody. And when Neil came to see my show, I talk about him only with love, and only with compassion, and only with, ‘Oh, poor Neil while I was going through this indecision about this abortion, he was just having to deal with me, and the indecision, and the back and forth.’ From my vantage point, he just comes out like this wonderful, heroic, sweet, loving husband. And I remember the first time he saw the complete show, he was upset, not at me, but he was like, ‘That’s… You didn’t quite tell it the way it happened, Amanda.’ And he’s come back to see the show again, and actually, we can now joke about it, and I know you were telling me a little bit about your sister, who’s not a storyteller, not an artist, and who gets to tell the story? Clare gets to tell the story. And Neil is a storyteller. And actually, it was only when I could put words to it that I think it calmed us both down. And I remember saying to him, I gave him the pass, I was like, don’t come see my show in Perth. You don’t have to sit through it again, it’s four hours. And also, since you’re Neil Gaiman, professional storyteller, and narrative controller, it really is your idea of fucking hell to be strapped in a chair for four hours.

Clare 38:21

I’m amazed he didn’t stand up and…

Amanda 38:23

And I have the mic, and I get to tell the story, and you don’t get to interrupt.

Clare 38:28

He must really love you.

Amanda 38:30

Oh, my God. And I’m like, it really is your personal hell, isn’t it, that I’m telling this story, and you can’t interrupt and say, ‘Well, it wasn’t quite like that, my suggestion is that we…’ or whatever.

Clare 38:42

See, this dance, I love hearing you speak out loud about this, cos you are both people who do put your work in public. Neil does it through fiction, but…

Amanda 38:52

Yeah, which is really different.

Clare 38:54

Yeah?

Amanda 38:55

It’s really different, and it’s a different zone. And putting yourself out through fiction, it just has a really different flavour than getting up on stage and saying, listen, let me tell you about my abortion story. It’s very, very different.

Clare 39:10

Those difficult, tender stories that often we have kept to ourselves, and people do keep to themselves, and that’s a coping mechanism for many, there are still whole generations of people who cannot talk about what happened in the war. And respecting that each person has their own way of living with life is one thing. When we as artists choose to live our lives this way, which is to say things out loud that may or may not include or involve other people, that’s one of the things that nearly stopped me from being an artist at all, or singing songs at all, that question of what right do I have to have an opinion here, and say it more loudly?

Amanda 39:54

Why do you think you’re so special, Clare?

Clare 39:56

Yeah, why are you so, why do you have such a compulsion, why is it so important that people hear what you have to say?

One of the saving graces in writing this book is I did have to blame my mum, actually, for the idea of writing it, because in that true Catholic ‘offer it up’ kind of tradition, when I was unwell, and my mum and all her mates were at prayer group for me, and she said to me one day, ‘You will use all of this one day. You will pass this on. You will use this for a greater good.’

Amanda 40:28

So you had to…

Clare 40:31

So we had to sit together for days, going through chapter two, which is a childhood telling of what I remember from Rowena’s experience of being unwell, cos my first memories of her, I have a couple, but most of them are at the children’s hospital, and feeling really bonded and attached to hospitals. I still wander into them, it’s really odd.

Amanda 40:56

That’s where everything’s gonna hopefully be made okay.

Clare 40:59

That’s the hope, exactly. And I thought, I loved her generosity spirit, cos we are very different people. This is my mum, Maria. We’re so different in the way that we look at the world, and the way we vote. We’re not different in the way we love, and we’re not different in our hopes for each other, and our hopes for what we do with our lives. And so, I gave her a first draft. Amanda, I did this, I thought, I can’t live and get this wrong, I’m gonna give her the first draft, I’ll give her this chapter, and I’ll just see if she’s got anything, if I got anything wrong technically, about the medical diagnosis, or something that I thought was said that wasn’t said.

Amanda 41:39

Fact check.

Clare 41:40

And I gave her some sticky notes, and I said ‘Mum, if there’s anything, you just make a sticky note.’ I mean, it was very carefully negotiated on both of our parts, and there was a generous generosity in the whole family about this, thank God. I don’t think that made it any easier for them, but they were willing to go there, and let me go there.

Anyway, a week later, I come back, and Mum said, ‘I’ve just made a few…’ Mum’s quite Dutch. ‘Just made a few little notes.’ And I look, and there are about 74 sticky notes sticking out of this one chapter, and my heart fell. I went, oh God, I’m never gonna be able to do it, and I despaired, because I had suffered for a year to try and write just this draft, and I did find that experience of writing profoundly delightful, brilliant, excruciating, horrific, all the things. But I went there cos I needed to do this thing.

Anyway, it turns out there were a few changes we made, but mainly it was just line editing, she’s quite a fine line editor. Commas, full stops, apostrophes.

Amanda 42:46

She was copy editing your book.

One of the other things that I was just thinking about when you saw me going into lala-land during your story, being in the laundry with your mom, and saying you’ll probably lose a child… The logic you have as a kid, I wanna tell you a story that happened this morning, cos I started thinking about Ash. I was actually a little late this morning too, we were both late.

Neil and I were in bed this morning, and Ash runs into the bedroom with a knife. Not a steak knife, a butter knife, but still, 4-year-old with a knife, not a good scene.

Clare 43:17

It’s a thing.

Amanda 43:19

He goes, ‘I want to kill you!’ And Neil and I are like, giggle giggle, this is cute, and it’s also really dark, but eh. And he doubles down, he goes, ‘I want to kill my parents!’ And Neil and I are like, ha ha, this is kind of funny, it’s also really…

Clare 43:36

It’s good he’s saying it out loud.

Amanda 43:38

Kind of not. And then he giggles, he’s naked too, naked with a butter knife. Runs out of the room, and Neil is already standing up, and I’m in bed, and I go, it’s your turn, you’ve gotta take that knife away from him. And Neil’s like…

Clare 43:53

Disarm that child.

Amanda 43:54

Yeah, and Neil’s like, ‘Let me get dressed first,’ and I was like, ‘You’re not gonna get dressed, kid with knife!’ So I hop out of bed, I run down the hallway. Ash is hiding, giggling, on a couch, holding the knife. And I look at him, and I say, ‘Ash.’ I put on my serious face. Serious mom face. ‘Ash, it’s not funny. I need that knife, right now. You can’t run around with a knife. It’s very dangerous.’

And he looks at me, giggling, again like this is all a funny game, clutching his knife, ‘But I want to be dead!’ I said, ‘No, Ash. Ash.’

I take the knife away, and I say, it’s not funny, Ash, and you don’t wanna make me angry, but it’s really dangerous to run around with a knife, you can’t…

Clare 44:42

Now you’re hiding the knife.

Amanda 44:44

‘But I want to be dead!’

And I look at him, and I get really angry. And I grab him, and I put him on a chair, and I say, ‘Ash. Do you know what it means to be dead?’ And he goes, ‘What does it mean?’

Clare 44:59

Oh, man.

Amanda 45:01

And I go, ‘Ash. When you’re dead, you just disappear. You’re not here any more.’

And he looks at me, and you know that thing when you totally silence a child? And he just… his whole face crumpled up. And then he lost it. (Screams) Like, he just started sobbing and wailing, and he threw himself in my arms, and he started shaking, and clutching me, and he looked at me, he was like, ‘I want to be disappeared! I don’t want to disappear! I don’t want to! I don’t want to! I want to be here! I want to be here! I want to be with you and dada!’ He just lost it. And then I lost it! Took a crying, sobbing child into the other room with Neil, and Neil was trying to make jokes about the knife, and I was like no, we’re past the knife now, we’re in an existential crisis. And we sat down, and for ten minutes, we held him while he wept, and told him how much we didn’t want him to die, and how mama didn’t want dada to die, and dada didn’t want mama to die, and he just had to go through it.

But it was so powerful to watch a 4-year-old having an existential crisis.

Clare 46:22

Well he really learnt, he’ll remember this.

Amanda 26:24

Oh my God, it was a good one. It was a great morning, Clare. Great morning in the Palmer-Gaiman household.

Clare 46:31

I know this territory so, so well, where we go there with the kid, with ours. And then we’ve got a similar dynamic in my relationship with my Marty, and he’ll come in and play when we’re lighting it, which has its health too, timing…

Amanda 46:48

Marty is your baby daddy.

Clare 46:49

He’s my baby daddy, and he’s my producer, and my manager, and all that stuff. He’s my man. My heart broke as you were telling that story.

The thing is this, that we can say to our kids quite often, but that’s very unlikely. I don’t wanna die, and you can say that’s very unlikely that you will die, and he will know that, really, because he’ll understand, you’ll explain to him, if you didn’t already, that dying is usually something that happens to older people. That grounding is important, and understanding death is terrifically difficult.

I think maybe what happens for kids where someone has died, or with Rowie, my parents could never say that convincingly, and say, it’s not likely that this will happen.

Amanda 47:35

Everything’s gonna be okay.

Clare 47:36

Yeah.

Amanda 47:37

Cos you knew it might not be.

Clare 47:39

And I’m trying to work out, as a parent, what’s the gift? What age do we tell them about this stuff? Sometimes the opportunity just comes upon us, and we take it. How important is it to their survival that they know this? Very important, I’d say.

Looking back at that, talking about that, you were crying. Do you feel that that, would you have done anything differently, if you look back now, was the right call to make at the right time?

Amanda 48:04

Oh, yeah.

Clare 48:06

He now knows something very important.

Amanda 48:08

And conversations sort of like this have happened with him before, because for whatever reason, he’s really into death, and killing, and graveyards, and zombies.

Clare 48:20

Gee, I wonder. I wonder why. You haven’t, by any chance, allowed him to be exposed…

Amanda 48:25

I blame Neil Gaiman. It’s just in the DNA.

Clare 48:29

Well, I’ve heard Neil talk…

Amanda 48:30

He’s just a dark, goth motherfucker. This 4-year-old goth.

Clare 48:35

But I’m gonna assume that he has a strong sense of what he’s doing, and the reason he tells stories the way he does is because he believes that there’s some things children should know earlier, that we protect them from, or that we, as a society, don’t allow them to process maturely until they’re… What do we think, a guy’s gonna get to the age of 15, and then suddenly be able to understand what these things are?

Amanda 49:01

More that it usually has a negative definition, but I am a pretty… I’m into mortality. I find it fascinating, I find our relationship with death, and dying…

Clare 49:15

It’s deeply directive too, isn’t it? I mean, do you find it makes you braver?

Amanda 49:19

It makes me feel very alive, thinking about death. And this is an old tradition, this is also, getting back to the book I was talking about, this is an old Zen tradition, is the more you meditate on death, the more vital you are! We are gonna die. Everyone right now on this planet isn’t… Check in in a few years, most of us will be gone. And having an appreciation for the fragility of life is really great for getting up in the morning, because you don’t take for granted that this is all a gift, talking to you, having a coffee, seeing the sky. Not everybody gets to do that, a lot of people are dead. So teaching that to a child, I don’t think there’s anything really morbid or wrong about it. And also, safety’s important. Don’t run in front of that car. Life is fragile, and you only have to run in front of that car and die once for me to want to say this. Cos that only has to happen once, you only have to lose your life once, for this conversation to be important.

At the same time, I don’t think you wanna burden. If you look at the lessons you had to learn, or maybe not even learn, but digest, you got the whole kitchen sink thrown at you at the age of 5.

Clare 50:44

There was just a bit missing in the middle. I knew that Rowie was gone, and I knew that, in our faith framework, that she was in a better place, so this was comforting. The reality of what had happened, I got to leapfrog to the comfort of thinking, maybe that hadn’t really happened. The bit in the middle was the bit that I struggled with, because who do you have those conversations with? It was the 1980s, and we didn’t have any real understanding of how to help children process trauma, or grief, or any language, how to help ourselves process trauma or grief. We’ve spoken about books a few times, and I remember the books on my parents’ bookcase were… There was like, two books on death. There was Elizabeth Kübler-Ross’s On Death and Dying, and there was another book called Life After Life, and that might be a Rabbi’s book about when bad things happen to good people.

Our language now, it’s so much more possible, and kids are allowed to process in a different way, given room enough to do that. So Ash will have so many more questions, and so much more to come back to you on, on that point.

My mum and dad were carrying on, and surviving, and doing actually a pretty solid job of holding things steady, but how do we speak into that space, and allow ourselves to come back, cos it’s quite common actually, for us to have experiences of trauma in our life. For some of us it happens early, and this is not to glamourise it, or gloss over it, but if we are able to find a way to go back in there, to sit with the corpse of it, as you would in Zen practice, we will come to know things that are hard to describe with words, that are useful to us, that are feelings. But I appreciate, in this day and age, I don’t have to go back in there alone. I get to go back in there with the other people who’ve been through it, or with experienced therapists, or with books that give me frameworks. We are in the most fortunate times, and still we suffer, and still we struggle, and still we wake up and look forward to a coffee.

MUSIC BREAK – Your Own Kind of Girl

Amanda 53:31

This seems to be one of the biggest things I have learned, particularly on this tour that I am just wrapping, which is, we can handle almost anything, the darkest of the dark, dark, dark, if we do not feel we are handling it alone.

Clare 53:48

That’s heavy work! You don’t just go and tap dance, and give high fives, and sing a little love song. To actually commit to going into this work with them, and feeling safe to lead them out and back into the world again, your show is for four hours, I just need to ask, what the fuck?

Amanda 54:07

Yeah, I don’t know.

Clare 54:09

Has this been what you hoped it would be, or has the cost of it been too high for you?

Amanda 54:14

Oh, no. The cost has been whatever, emotional and energetic, and I’m a little exhausted all the time, and there’s way more lines on my face than there were at the beginning of this tour. I’m so happy that I did things this way. The same way, I imagine, you are so happy you wrote this book, even if it exhausted and frustrated you in the process.

Clare 54:41

Yeah, but I’ve had a year in between. You’re in the middle of it still!

Amanda 54:44

I’m still in it. A performance is so different from a book. Because I also wrote a memoir, and really agonised over it, and struggled with it, and then it was done, and I remember pressing send on that motherfucking final approved draft to the publisher, and going, oh my God, I can’t believe this has an ending!

Clare 55:03

It’s done! It’s done!

Amanda 55:04

It’s done! And a performance like this is never quite done. I change the draft of the script of the show every night, including now, part of act 2 is talking about Aboriginal rights and bushfires and all of the sexual assault stories that I heard down in Tasmania, and you’re just like, this endless trawler of pain, picking up… You can’t help but just pick up as you go along…

Clare 55:32

You’re like an alchemy machine.

Amanda 55:34

Exactly! And then everything has to sort of be incorporated, or at least that’s the challenge that I give myself, because I could have just written a simple script 18 months ago, and said, this is it, I’m tying a bow on it. But instead, I feel like I have to incorporate everything, or it feels inauthentic.

And now that I am done with the tour, it’s finally, really, really, really good, and I only have 4 shows left in New Zealand! And I’m like, ahh! And now what? Because now, it almost feels like I’m ready to press send, cos the draft is finally copy-edited and finished, and every story fits in the hole, and now I’m done, and now I’m ready to show it to the world, but fuck, my tour is over!

Clare 56:21

How would it be, have you filmed it at all, would you film it at all?

Amanda 56:25

I think that’s the key, is to hopefully do one final run of it, and film it. But also, I basically did this tour, saying…

Clare 56:32

That’s a DVD boxset.

Amanda 56:35

When I’m done with this, I’m never gonna do it again, but now that it’s in really good shape, I’m like, maybe I should go do a festival run, maybe I should go do it in a theatre.

Clare 56:42

Why did you say you were never gonna do it again?

Amanda 56:44

Because it’s fucking exhausting! Because, actually, sitting with that kind of darkness for 4 hours every night, while it is incredibly cathartic, there also is this question of, okay, well where’s the line? Where do you stop rehashing the past, and living in the story of darkness and trauma, and get to the good part, where you get to be done with your trauma, and you get to just go have your fucking coffee, and tap dance with your friends, and get a little bit of light in your life. Because I think it’s dangerous, and I am not a superstitious person at all, but I do think it can be dangerous, to sit too long in the dark. Shit can get moldy. You gotta air it out.

Clare 57:35

See, you’re airing it in public, and then are you doing that consciously, and purposefully, because your art is about serving, you’re there to serve and tell stories. This is why people who do this kind of work sometimes have struggles with how the hell to shift off. At the end, the thought of having something that would help you get into a different mood state really quickly is very, very attractive. But what do you do? You’re a mum now, you’re out there, you’re gonna be woken up by a small child in the morning.

Amanda 58:08

Well, I think if I have learned anything after 20 years of being a performer, and also on this particular tour, at the very beginning, I was so exhausted, by the process every night.

Clare 58:21

I love the way you said that word. Exhausted.

Amanda 58:24

By the process every night, that I was like, how am I gonna do this? I could barely even talk to people after the show.

Clare 58:30

Well then you should have a small cupboard in every single… A hiding cupboard, where you just get to hide for a little bit after!

Amanda 58:37

But then, I noticed it was sort of like a muscle. Code switching between ‘this is the four hours that I talk about trauma, grief, abortion, miscarriage, death,’ and the amount of adjustment time that I needed to go back into tap dancing coffee world, would get shorter and shorter and shorter and shorter, to the point where I couldn’t believe it, but by the time I was doing my shows in London, it was just like, the minute I stepped off stage, everything got left on stage, and it was a totally, a great place to entertain 40 people, oh my God, darling, how are you? I am so glad you were so touched by the show, why are you crying, do you need a hug, do you need a tissue, do you need a drink? I can take care of everybody now because I am so fucking good at leaving that where it needs to be.

Clare 59:26

And then what happens? So then you say goodnight, you get in the car, you go to your hotel, then what happens?

Amanda 59:32

Bath, bed.

Clare 59:33

Done.

Amanda 59:34

Bath and bed. And also, I have been saying no to every single opportunity that has been handed to me post-tour, because I have built a fence around a few months of time where all I do is home, tap dancing, coffee, child, friends.

Clare 59:52

I might make a little album in there.

Amanda 59:55

Well, that was an accident.

This morning… So, it was 10:30, we were supposed to meet here at 10:30 for the podcast. I texted you, hey, I’m downstairs, are you here yet? And I had this spidey sense. And the minute I saw your little bubble, and then you were like, fuck, fuck, fuck, hold on a second. And I was like, she forgot. She either isn’t gonna be able to make it, or she’s gonna have to scramble all the way down here from north Melbourne, what’s gonna happen?

You called me, which was so great, instead of texting, and you just told me the truth. My kid is sick, I thought it was Thursday, it’s Friday, I’m so sorry, I’m on my way. I so appreciated you being so honest. But can you do me…

Clare 60:37

I was in the shower! I was literally in the shower!

Amanda 60:42

Why were you checking your texts in the shower?!

Clare 60:44

No, I heard a ping. I was listening to a podcast, and I heard a ping, and then my conscience must have kicked in, (gasps) ahhh! And I went, my darling…

Amanda 60:43

Because you have done so much work around anxiety, and being triggered, and the shame spiral that can happen, and this is not as punishment.

Clare 61:06

I love it.

Amanda 61:07

This is because it’s such a fresh, good opportunity to talk about something teeny-weeny…

Clare 61:09

Hit me. Love it.

Amanda 61:11

And I have a billion of my own like this, because I can be very forgetful and misplaceful… Tell me what’s the first, second, third, fourth thought that goes on, and how you manage a moment like that?

Clare 61:31

Great question. Amanda, thanks for the opportunity to…

Amanda 61:34

You’re so welcome.

Clare 61:35

Firstly, fucking apologise. I’ve gotta start here, I don’t like being late, I don’t like letting people down, and my life, like most working mums and dads, is many moving parts. And I’m heavily reliant on my calendar, and on my crew, who often fill in my calendar for me. It’s been a funny old week, and I woke up this morning, first thing I would normally check what’s going on with the day. I woke up to a cat jumping on my head, and then my son calling me, it was quite weird, he’s two rooms away. It was quite early in the morning. I went, that’s odd, and I picked it up, and I could hear…

Amanda 62:13

How old is he?

Clare 62:14

He’s 13. He’s had a sore throat. He loves school. So he was sick. Got up, someone was cooking an egg. Anyway, the day got away from me, and my head just said it was Thursday. And Marty had rushed off in the morning, he’s like my frontal lobe, which is a terrible thing to say, but I think this is how we’ve learned to function. He’s very detail-oriented, and I’m big-picture-ish.

So anyway, kids are off to school, everyone’s off to school, Ash has got an exam today, my girl. Eventually jump in the shower, I think I’m having a lazy day at home with my kid, with something in the afternoon. I’m in the shower. I see your message. I think… no, it’s Thursday. And then I think, hang on a minute. And I check, and I realise it’s Friday. Fuck, fuck, fuck, I say to you.

And now, here’s the difference. So that was a long lead up. I knew it was you for a start, and I know that you understand these things, actually. That when you have a life like this, there are lots of things going on, and sometimes you drop the ball on a little thing, and I knew that you’d get it, and that if you could accommodate waiting 25 minutes for me to get there, you would. So I had that feeling, I knew that to be true. In the old days, I would have just caved in on myself. I would have got there in 25 minutes still, with my hair wet.

Amanda 63:38

Yelling the whole time.

Clare 63:39

Yelling the whole time in my head about what a stupid idiot I was, and how profoundly disrespectful, and I’ve ruined everything, and it would be very dramatic. These days, after that many years of parenting, and surviving, I just went, yep. Fucked it up. I’ll do my make up in the car. And from the moment you texted and said, do you need a coffee, I knew we would all be absolutely fine.

So that’s the difference now, I am a little kinder to myself, and more playful. I used to think that I was gonna get it all right, and I used to think that I’d failed if I hadn’t. In the same way that I used to think, one day the voice of Frank would go away and disappear, and that would signify true success.

And then I also used to think I could somehow escape death. I’ve thought all sorts of things, and I could change all sorts of things in my life that I’m not able to. So I work within that powerlessness, and I work within the fact that I’m gonna fuck things up, and I’m gonna show up anyway, and I’m lucky to have forgiving friends.

Amanda 64:43

Do you find that you also know how to deal with people when they are dropping the ball, or whatever, and since you’ve been there so many times, you know how to ease other people’s anxieties, because you’ve been there yourself?

Clare 64:59

Yeah. Well, I had a radio show for two years here in Melbourne, and we had 24 different guests each week. And people have lives, sometimes things happen, people get sick, they forget, or they’re very, very nervous. So I think probably the best thing that I’m able to do, and you’ve got this gift too, you did it with me, you didn’t punish me, and you weren’t gonna punish me. I mean, that’s the worst bit, isn’t it, when you’re like, I have fucked up, and I’m gonna get punished by someone else, and shame my family, and reputation.

Look, a reputation is based on integrity, and that’s when I… When I have someone in the room with me who’s nervous, I just remind them that we’re okay, and as soon as playfulness is in there, we’re alright too. We’ve spoken about a lot…

Amanda 65:51

Humour is key.

Clare 65:52

Yeah. Spoken about a lot of pretty difficult stuff today, but I think one of the things that I will be doing, and you will be doing too, is I’m off the hook. I get to tell jokes for the rest of the day! We’ve done our deep work!

Amanda 66:06

We’ve done our work.

Clare 66:07

And I did try to take that approach too, with the book that I wrote, and with everything that I do. We’re light and shade workers. We’re trying to talk about profound things, or real things that don’t sink people, and we’re trying to add some levity to it as well. Our world is in a fricking intense moment in time. You and I were just talking to ourselves about the virus that’s going round, we’ve had the bushfire, we’ve had an extraordinary time of disruption in world politics. There’s so much going on with our climate. We’re gonna keep putting one foot in front of the other. We’re alchemy makers, we are attempted buddhists, we can do whatever we need to do to keep putting our hope into the world.

So I wanna thank you for everything that you do, Amanda, sorry to just be mushy, but I need to do that.

Amanda 66:58

No, let’s be mushy. And I loved that I randomly ran into you right after I got here, and then your book was right there in the bookstore, and I was so happy to have this book in my life, as part of my trip here.

Clare 67:15

Did I tell you that only a few days before I saw you, walking around the streets of my home town, and you and Neil were walking? I had, of course, thinking of you, I had listened to your Rich Roll podcast. Then I’d got a MasterClass, I’d been watching Neil’s MasterClass, and it was only…

Amanda 67:35

You were already hanging out with both of us.

Clare 67:37

I was already hanging out with both of you.

Amanda 67:38

Psychically.

Clare 67:39

And feeling I truly was, so then when I saw you, it wasn’t such a surprise.

Amanda 67:43

Well, your book is fucking phenomenal, and one of the things that I really do love about it is that it is a gorgeous combination of heavy and light, and it’s really, really fucking funny. Your vulnerability and your confidence are in there, just in a gorgeous dance, and I loved reading it. The book is so comforting.

Clare 68:03

Thank you, so, so much.

Amanda 68:06

I’m gonna send you guys out on a recording that Clare and I just did together.

Clare 68:12

What a treat.

Amanda 68:13

A cover of a song called Black Smoke by Emily Wurramara that was on the Bushfire benefit album that I put out.

Clare 68:18

She’s a brilliant Australian, young Australian singer-songwriter. Such a glorious sister.

Amanda 68:23

So, here we are, it’s me and Clare, singing together in beautiful, desperate harmony.

Amanda 70:16

This has been The Art of Asking Everything podcast.

Thanks to my guest Clare Bowditch, check out her music, book, and other things at clarebowditch.com

Our interview was recorded by Nick Edin at Sing Sing Studios in Melbourne, Australia.

For all the music you heard in this episode, you can go to the new, improved amandapalmer.net/podcast.

This podcast was produced by FannieCo.

Lots of thanks, as usual, to my amazing team. Hayley Rosenblum, Michael McComiskey, Alex Knight, Jordan Verzar, and introducing Kelly Welles, who’s been helping me newly on the social medias.

And last but not least, this whole podcast would not be possible without patronage. Like I said at the beginning, this keeps us ad-free, sponsor-free, endorsement-free, weird-corporate-podcast-world-free, so please, if you’re not already backing, come in, it’s a dollar a month, and just having you there, and knowing that your support is there, means the world to me.

And special thanks to my high level patrons: Simon Oliver, St. Alexander, Birdie Black, Ruth Ann Harnisch, Leela Cosgrove, Robert W. Perkins. Thank you, all of you, whether you’re in for a dollar, or more, for helping me make this podcast.

Things are going to evolve over the next couple of weeks and months, so stick around, and see what happens, I’ve got some really exciting guests coming up in the next while. So, so, so excited!

Thank you.

Signing off, this is Amanda Palmer. Keep on asking everything.