Fred Leone: Song Man

This podcast is patron-funded and ad-free! Please support us on patreon for as little as $1. For a post about this entire podcast (stories, photos, links, reading list, transcript and more) go to: https://www.patreon.com/posts/how-important-is-44587373

EPISODE 16 OF THE ART OF ASKING EVERYTHING: Fred Leone: Song Man IS OUT NOW WHEREVER YOU GET YOUR PODCASTS.

Here’s a link to all the places you can get and subscribe to the podcast: https://linktr.ee/AskingEverything

Twelve months ago, the Australian bushfires were center stage. I was in Australia for the final leg of the “there will be no intermission” tour and all that mattered was raising money to help the effort. With the support of my patrons, we made Forty-Five Degrees: Bushfire Charity Flash record and on March 8th 2020, we staged a fundraiser.

I recorded this interview with Fred Leone, who participated in both the record and the fundraiser, two days before that show, and less than two weeks before Covid really upended the globe. A conversation about the marginalisation of first nations Aboriginal Australians and their culture might have lost its impact after the craziest year in living history, but you know what? It’s all so fucking RELEVANT. Our ability to communicate with each other well – through words, through music – is the glue that holds us together and if we can learn anything from recent events in the US, it’s that Western culture’s glue is no less vulnerable to erosion than any other.

Fred has worked for years to preserve the language and rituals of Aboriginal culture, through the traditional means of storytelling, music and art. We talk about how tech has usurped these channels, how it might be repurposed to reopen them and how swiftly their disruption leads to extinction. It’s weird how a conversation can be so sad and yet full of hope. And Fred’s voice…I could listen for days. I hope you hear the music under it all. It’s more important than ever to keep sharing our stories and singing our songs. It’s our light in the dark.

Show notes:

Description

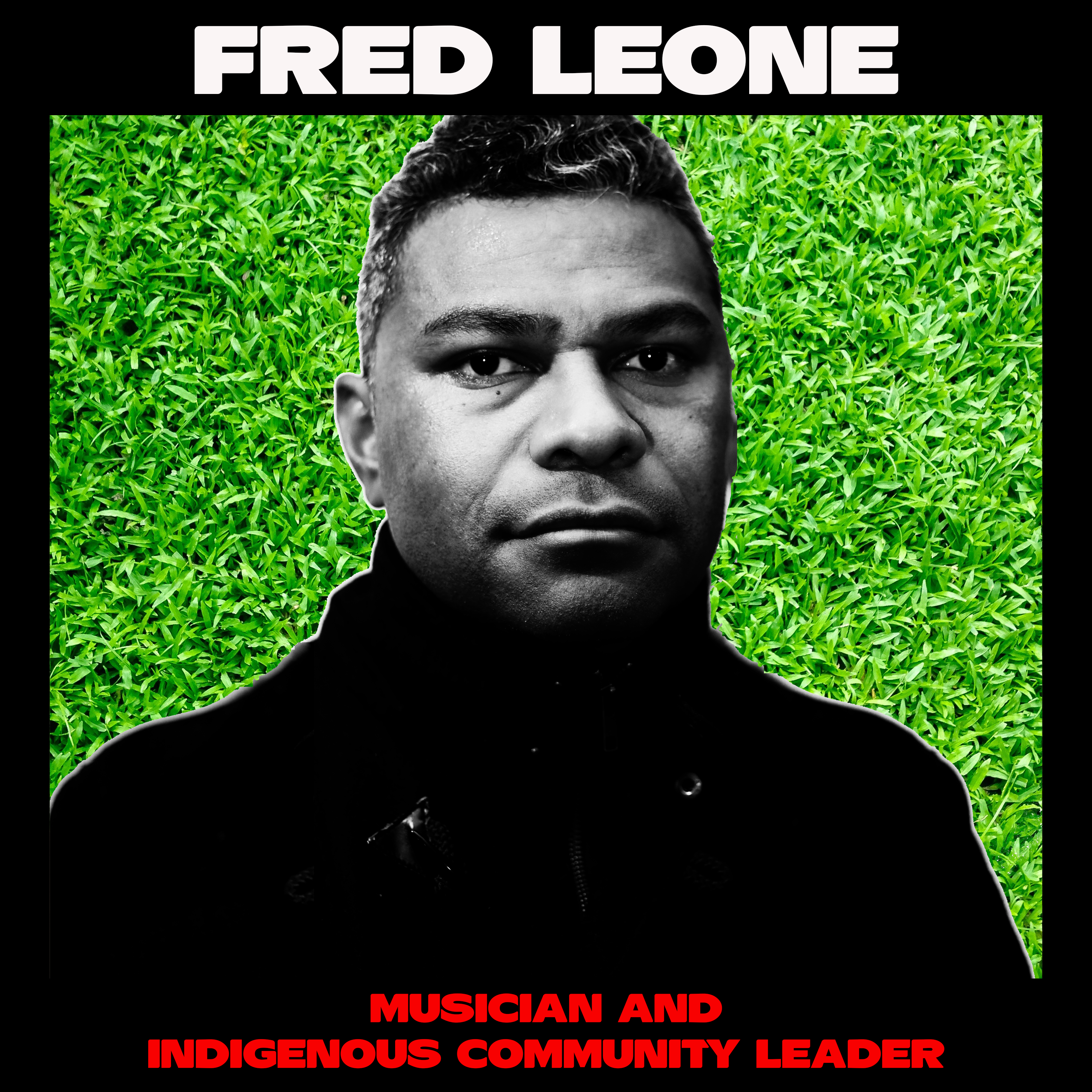

Fred Leone is a musician and artist with traditional ties to Butchulla and Waanyi Garawa country and is of South Sea Islander descent.

He is the frontman for the hip-hop group Impossible Odds, which expresses issues facing aboriginal people through music.

Fred is also a leader in his community and a First Nations advocate.

He is committed to passing down the cultural knowledge of his ancestors by passing on traditional songs and dances to younger generations via his work as a song man.

CREDITS:

Thanks to Fred! Check out his music on Spotify!

The engineer for this interview was Nick Edin.

For all the music you heard in this episode, you can go to the new and improved amandapalmer.net/podcast

This podcast was produced by FannieCo.

Millions of thanks go to my incredible team:

Hayley Rosenblum who makes all things possible — she is the ghost in the machine in our Patreon and also makes sure everything else gets done — words, pics, live chats, and general internet love. I could not do this without her.

My assistant Michael McComiskey who makes sure all the trains run on time and that I am able to do all the things, all the time…

#MerchQueen Alex Knight who is helping us transcribe so these conversations are accessible to ALL!

Kelly Welles on social media!

And, of course, my manager Jordan Verzar who brings it all together.

And last but not least, this whole podcast would not be possible without my patrons. At current count, about 15,000 of them. They make it possible for this podcast to have no ads, no sponsors, no censorship, no bullshit, we are just the media, doing what we do. So special thanks are due to my high-level patrons, Simon Oliver, Saint Alexander, Birdie Black, Ruth Ann Harnisch, and Leela Cosgrove, and Robert W Perkins thank you guys so much for helping me make this.

Everyone else, please, go to Patreon, become a supporting member. This will also give you access to the follow up live chat that I’ve been doing with every guest a few days after the podcast comes out. The podcast comes out on Tuesday, the live cast is usually Friday. You can follow my social media or the podcast page for more information.

The Patreon is also full of extra things, and pictures, and all sorts of goodness, and you will get the podcast right, plop, in your inbox.

Thank you so much, everyone.

Signing off, this is Amanda Fucking Palmer. Keep on asking everything.

This podcast is 100% fan supported. There are no corporate sponsors or restrictions on speech.

No ads.

No sponsors.

No censorship.

We are the media.

Exclusive content is available to Patrons only.

Go to Patreon.

Become a member.

Get extra stuff.

Join the community at patreon.com/

FULL EPISODE TRANSCRIPT:

Amanda Palmer 00:34

This is The Art of Asking Everything, I’m Amanda Palmer.

It’s January 11th 2021, as I record this. Happy new year, everybody. Oh my God.

I wanna tell you a story. A few days ago, while I was looking through my phone to find photos and video clips for the post for this episode, I came across a clip that I had forgotten about, from the day this was recorded, and it was Fred Leone, my guest, playing while I sat and listened.

MUSIC CLIP: Fred playing a song for Amanda

Amanda 01:38

I found this clip the day after the Capitol building in my home country of America was stormed and defiled by a bunch of assholes. For reference, I’m in New Zealand right now, very far from home, and I was just feeling all the raw pain of this moment.

And it was amazing to me how just listening to this sound calmed me. And I thought, I’m not gonna wait until it’s time to “promote” this episode, I wanna share this and put it out into the world. So I put this little video clip up on Instagram, and somebody wrote in the comments, “I love this because you can hear the magic and soul connection in his voice.” And I thought yes, that is it, there’s this thing about music, sometimes it just transcends language, and time, and space, and place, and we can’t explain, of course we can’t, and that’s why it’s music.

There’s a little background: I met Fred Leone through my manager in Sydney, whose name is Jordan Verzar, and he is a beloved long-standing member of my team. And Jordan knew that Fred and I would connect with each other.

Here’s Fred’s official bio: Fred is a musician and an artist with traditional ties to Butchulla and Waanyi Garawa country, and he’s also of South Sea islander descent. He’s the frontman for the hip-hop group Impossible Odds, which expresses issues facing Aboriginal people through music. And he’s also a leader in his community, and a First Nations advocate. He says he’s committed to passing down the cultural knowledge of his ancestors, by passing on traditional songs and dances to younger generations through his work as a song man.

And when I met him, you’ve gotta remember, the bush fires were all anyone was thinking about, they’d ravaged his country. And I was in Australia touring at the time. Now let me note the date of this recording. It was March 6th, 2020. And we were at Sing Sing recording studio in Melbourne, Australia. This was less than two weeks before the COVID madness really struck. And everyone in Australia was fiercely focused on the bushfires. And I was only a few days away from doing an event, a charity event, with Fred, that was a benefit concert for the bushfires. But the money didn’t go straight to relief. It went to an Aboriginal group called Firesticks, which educates people about cultural burning. About how to work with the land, as the Aboriginal people have been doing for tens of thousands of years, instead of just plundering it and ravaging it, in dialogue with the land.

And as I think back on this moment, and this discussion with Fred, and the benefit, and that whole time, I think about how music, and knowledge, ritual, education, these things that we’re supposed to pass down, this important information, how desperately we need music, to be able to heal and continue. Not just immediate music that helps us and comforts us, which is important, and music is amazing at doing that. But this other, bigger thing that music does, when it acts as a bridge, and the connector, between people, through time. The thing bigger than language and the printed word.

And I think there could not be a better time to put this episode out, when we need so much healing. I hope you love it. Everyone, please welcome Fred Leone: Song Man.

Amanda 05:46

Fred, thank you for coming and being part of this podcast.

Fred 05:50

No worries, thanks for having me here.

Amanda 05:51

Before we get into it, I wanna listen to a song, that I think is well over 10 years old now. Tell me a couple of things about Laugh It Off, and how you wrote this song.

Fred 06:01

Growing up, Aboriginal people in Australia seemed to have, we call it like, fellas too comical, or that’s just comical, and so there’s this way of dealing with extreme tense situations and pressure by just sort of, at some point someone will turn it around so there’s something everyone can have a laugh at.

But this particular song was about some young neighbours that I had, rented a place next door, and invited me over for beers one Friday night, and they had all their friends there. And one of the guys turned round, he said, oh man, you’re so cool, and that’s why I invited you over, you’re alright, but those others, they’re lazy, smelly, and they whinge. I’m not racist! And then I was like… ugh.

And then I wrote this song, and then it got high rotation on Triple J, and was on Qantas international in-flight radio, it went around the world, and I thought, just laughed it off at the time. I could have lost my shit, but I wrote a song about it.

Amanda 07:03

Yeah, let’s listen to it.

Hey boys and girls, here’s a bit about me

Fred Leone, nowadays known as Rival MC

Back in the day growing up, I got teased just because

Could never put a finger on just what it was

Til I was told one day, it was because of my skin

I mean you’re alright, but those others, they’re lazy, smelly, and whinge

I cringed, thinking I should knock this fella’s block off

Kept my composure and just decide to laugh it off

Amanda 07:28

When you listen to the message of this song, is there any part of you that has changed your opinion about laughing something off versus having some kind of degree of righteous anger?

Fred 07:42

I’ve changed heaps now. That was a while, that must have been about 2007, a long time ago. And yeah, that righteous rage… I just channel it into healthy outlet, or in a way, spin it into a narrative where people can understand, give them a clear snapshot of why something might be totally fucking infuriating.

Amanda 08:12

What were your major hip-hop love influences?

Fred 08:15

Public Enemy, NWA, when I was little, yeah, NWA, my older cousins played NWA. There were no Aboriginal role models on TV. Once every few years, Ernie Dingo might pop up in a movie or something. There was no Aboriginal, Australian Aboriginal, First Nations mob on TV. So the only black people that popped up were these rap stars. And they were talking about stuff that I was seeing in my own community. The only difference was at the time we didn’t have crack, we’ve got crack now. We call it ice. And we didn’t have guns. But everything else was relatable, like the characters, the people, the music, and the struggle, I could relate to as a young person.

Amanda 09:00

Where did you grow up exactly in Australia?

Fred 09:02

Between the northern suburbs of Brisbane, moving around in black housing and housing commission, and then Inala, late 80s, early 90s, had the highest crime rate in the whole country. Around Inala, mainly the outer suburbs, cos everyone from Inala was doing the stuff in the suburbs around Inala. And a melting pot. So it’s not just the indigienous people living there, there’s white kids, Vietnamese kids, Italian, Albanian, were all living in housing commission, nobodys got any money, everybody’s bored, what do you do?

Amanda 09:40

What did you do?

Fred 09:41

Really stupid stuff. It was weird because it was very much like a Robin Hood mentality. So if they’d say come through, he’s come through with cash. So suddenly he had 25,000 bucks. Then he’d be in a maxi-taxi, dropping off food to my aunties, his aunties, his family, a Vietnamese mate’s houses. And that was the thing to do, everybody did it. We were all just one big crew of people, for whatever reasons, were stuck in this situation where there was no opportunities to get out of the community, and so everybody just sort of stuck together.

Amanda 10:20

So I’m thinking about the listeners who don’t really know very much about Australia, don’t know much about Australian history, Aboriginal history. What’s the primer that you would give to, say, a teenager in America who hasn’t learned any of this yet, and wants to know the basics of indigenous Australian culture?

Fred 10:45

Look at first contact, so colonisation of Australia. The context of colonisation globally. Australia was colonised by England, by the crown. And then within the context of the last 250 years, 230 years, 250 years? Assimilation, dispossession. In there there’s also massacres, and wars, internal warfare, guerrilla warfare. It’s only in the last 200 and something years. By international standards, a “young” country, but the history beyond that goes right back, through song and dance.

Amanda 11:29

You come from Butchulla people.

Fred 11:31

Yeah.

Amanda 11:32

Can you explain what that means?

Fred 11:33

Before colonisation, there was 300, roughly, tribal groups. But within those language groups, they call them language groups or tribal groups, pretty much like Europe, so you can go to different sections of Europe, and everybody’s speaking a different language, it’s the same here, across the whole continent. All up, there’s 6 to 700 different dialects, across the whole country. On the Butchulla side of my family, we’re from K’gari, from Fraser Island, which is well known tourist destination, and then on my grandfather’s side, we’re from up in the gulf of Carpentaria, several thousand kilometres away, up in the gulf of Carpentaria, in the Northern Territory. So one’s dry, they get a wet season, they get monsoon wet season, and the other area’s sort of subtropical. So it’s… the humidity is what hits you too.

In the context of Captain Cook landing, and then the process of annihilation basically, there’s best practice models that were taken from every other country that England colonised before they got here, we’re the last man standing so to speak, in terms of an independent country of people, so all the best practice models were set into play by the time the British came to Australia.

And then, in the States they have reserves, in Australia we have missions. And so missions were set up, and then missionaries were sent to those outposts. If there were survivors, they massacred some people cos they wanted to put cattle there, and those people wouldn’t give up land, and they’d get massacred, and the ones that survived, the warriors that survived, instead of just taking them and putting them all in one reserve, three of you are gonna get sent to Victoria, three of you are gonna get sent to South Australia, three of you are gonna get sent over to WA, and just split them up. And so what that does is then, you drop 30, 40 different language groups into a community where they’re not the traditional owners of that community, they’re not the traditional people of that land, they can’t speak that language, there’s conflict, and so they went, okay, we want you to all get along, so assimilate. Here’s a bible and here’s English, and that was it.

Then you had things like the Opium Act, so there was an act, when the gold rush started, and the Chinese came, with the gold rush, with people from Europe, then government were like, okay, well we need to sort this out, so they brought in a law called the Opium Act, so you could pay Chinese and Aboriginal people with just opium and alcohol, you didn’t have to pay them.

Me personally, I feel like some Aboriginal communities are really dysfunctional today, and I feel like we didn’t have that renewal of people coming, like with the Chinese community, there was always people coming and renewing it, and making sure that the cultural practices and stuff were staying strong, and those communities were building, and the Opium Act, the effect of it, I feel like, didn’t hit home as hard as it did in Aboriginal communities, because there was no renewing or refreshing of new people coming, it’s like, this is all we had. There’s only my great grandfather’s era.

My great grandfather survived three massacres, the last one was in 1896. He was a part of wild time, so when Australians were moving up into the Northern Territory, there’s a place called Hell’s Gate, and that held off settlers for 30 years, called Hell’s Gate. The military would only take people to that point, and they said, after this, you’re on your own, if you wanna go dig for gold, or farm, or take your cattle out, this is it. We’ll only escort you to Hell’s Gate, and that was the gateway to the Northern Territory, and all up to Arnhem Land and everything. And 30 years, there was a 30 year conflict, that my great grandfather and my great great grandfather, they saw it in their lifetime.

Amanda 15:32

Just definition-wise, what does it mean to be a song man?

Fred 15:36

Ah, a song man is someone who keeps the stories alive, and so from a young age, you’re sort of keeping an eye on older song men, older people that are holding that knowledge, are watching the young blokes in the community, and I just happened to be one of those guys. Obviously I was always singing, I was always rapping. But also, I’d sit there, and if my older brothers were singing songs in language, I’d just learn the song. And so, learn the song, I was always interested in it.

And so then those stories, older people will watch, and I’d call the process fishing, so I’m doing it now. Sadly, I had one of my nephews who I was imparting songs to, and my brother was imparting songs to, and then he ended up going to jail, and he came out and said, this is your last chance, if you mess this up, fuck this up, no more of your grandmother’s tongue. And then he did it again. And so, said no. And it was the most heartbreaking thing, cos when you think about it, our languages and our culture… it’s close to extinction. On my grandfather’s side, there’s maybe five speakers, full speakers of that language. And they’re all 70, 80 plus. So they’re getting old, and they’re gonna die. But the younger people, even my age, in their 40s and 50s even, and under us, been seduced by technology and stuff, and drugs and alcohol.

Amanda 17:20

So who’s there right now? Who’s there to catch the language?

Fred 17:23

On the east coast? I know everybody. Everybody knows everybody, you can count them on your hands and toes how many people there are. Arnhem Land, there’s a whole bunch of people, so it’s strong. WA is strong. Just depends, Central is strong, but say, out of 300-and-something language groups, there’s probably twelve that are strong. The rest are in all different states of flux, all different states of extinction. But being a song man, you get that knowledge, so it’s just trained into you since you were little, like you just learn these songs, you learn exactly what country it’s from. It’s all these other little intricate things that take place in your brain.

Amanda 18:11

This is interesting, you talk about getting seduced, or whatever, your cousin being seduced, and you definitely got, maybe seduced is the wrong word, but you listened to hip hop from Compton, Los Angeles. This is not your community, aren’t really your people, and yet, something about it really spoke to you. Where do you see that hazy boundary between, oh my God, there’s so much to seduce you and take in, and now I have access to the internet, and now I have access to hip hop, from all over the fucking world, and oh my God, there’s so much out there, and on the other hand, this teeny, fragile, little thing, that feels like a fire not tended to, oh my God, it’s just gonna go out? You’ve probably had your own struggle with this in your life, like how much out, how much in?

When you’re looking at someone who’s 20, and has access to literally everything because they’ve got a smartphone, how do you teach them to balance out between the seduction of the whole wide world, and that’s your fucking grandmother? Listen to her, she has a story to tell you, and that story belongs to you!

Fred 19:12

Yeah, once she’s gone, it’s gone, you know? There is no, ah, I’m just gonna get on anytime and download the information I need, once she’s gone, she’s gone.

So the first part of your question, there was this analogy I put together, and I said, I say it to young people, with hip hop in particular, cos that was my thing, I’m a part of that subculture, supported Public Enemy and Dead Prez, people like that, and hung out with Brother Ali, and so I feel like that’s a part of who I am, and that’s a part of, I belong to that subculture, but also I belong to my culture, and some people often ask how? How does that work?

I look at it like this. In rap, you have an MC. In Aboriginal culture, we’ve got a song man and song woman. In hip hop, you have break dancer. We have shake a leg. In hip hop, you have the DJ. We’ve got the didge. In hip hop, you have graffiti, those are the four elements. In our culture, we’ve got the oldest graffiti on the face of the planet. When it comes down to the crunch, that’s why it was so accessible for me, I think, and young indiginous people in Australia, young First Nations people in Australia.

Amanda 20:19

I read an interview with you where you were talking about the fifth pillar being knowledge. This is about passing on knowledge to the people around you.

What’s funny, I don’t know how much you know about Neil, about my husband, but he thinks a lot about stories, what they do, why they matter, and he was talking at the literary festival about, and I know you know this, cos I’ve also seen you talk about this, these stories, here, are the oldest ones. These stories go back God knows how many generations, how many years, how many thousands and thousands of years. It really does make you wonder, are we being careful with how we’re sending these stories on, into the future? What’s the best package? Is it hip hop? Is it poetry? Is it dance? Is it no, we just need to have a really fucking amazing internet infrastructure with every little Wikipedia fact etched in some kind of material that won’t die?

What do you make of this collision with the oldest culture in the world, and the newest technology, and how they can aid and abet each other?

Fred 21:37

Yeah. I think it’s happening now, it’s slowly happening with animation and things like that, and making sure that the core old stories, old songs, old narratives that have been there for thousands of years, are kept, and being able to be passed on. But, if Aboriginal people were a koala, koalas are nearly extinct. Aboriginal people are nearly fucking extinct! First Nations Aboriginal Australians are nearly extinct. We’re still here, but once your language dies, the culture dies, because then you don’t have that connection, that connection is lost. Learn that, even in linguistics, so that’s in a scientific setting, in linguistics, they talk about it, we talk about the connection between language and a culture.

If we’re gonna worry about the koalas, we’ve gotta worry about this. This is the oldest culture on the face of the Earth, but it’s the oldest, as human beings we’re all here, and we’ve all been a part of the Earth for around the same amount of time. Except in Australia, what was a little bit different is each clan group stayed in one area, and was responsible for one lot of stories. In our family, we know if the black wattle starts flowering, we’re gonna walk down and we’re gonna catch fish, so look for warmer for the bird. Once the bird starts to drop, then we’re gonna, and that’s just from thousands of years’ observation, and just passing that knowledge down, just drilling it into people’s heads, about this is what happens on this section of land here. It’s different for that other mob, so they do whatever they do. And so, that knowledge passed down from generation to generation is…

Amanda 23:18

You can’t have culture without language. But also, place is really important. But also, you see this, I mean certain cultures are just diaspora, and we’ve managed to be a culture without a place because whatever, we’re on the run, or what you were saying about the Australian government, or whatever, the British government back in the day. Divide and conquer. Take language away, take land away, erase culture.

Fred 23:45

Yeah. And then, in a weird twist, hundred years later, turn around and go, okay, knowing that families have been moved and taken as a part of legislation, we’re gonna move them round the country, and then say, okay, well, we’ll give you native title and land rights, but you have to prove your unbroken connection to that part of the land. When they’ve just spent two generations in another place.

Amanda 24:08

Can you explain land rights, versus sovereignty, and what this would mean to someone in Australia who’s an activist?

Fred 24:19

Yeah. So land rights was a time in the 70s, 80s, when the government of the day decided, okay, Aboriginal people have rights, they have land rights. Land rights is anything that’s not already built on, they own it, they own it outright, there’s no and, ifs, buts, or maybes. But once people started… They didn’t expect for the rush, for people to go, actually, we do know all our stories, we’re gonna show you, in a court of law, in a federal court, in the highest court, in the high court of Australia, we’re gonna show you that yeah, we have these connections to the country, to the land, and these are the songs for that land. This is a creation story for that mountain, that river, that section of the ocean. These are stories that have been handed down, generation to generation.

That happened, and then it only happened for a short window before the government went…

Amanda 25:13

Oh shit.

Fred 25:14

Oh shit! Okay! Well, let’s move the goalposts, okay, suddenly, oh no, we’ve changed it now, it’s called native title. And so, native title is a watered down version of land rights. So in native title, the government, you’re acknowledged as the traditional people, and they can consult you if they wanna do anything on your country, but it’s not gonna stop…

Amanda 25:39

Them from just going in there and drilling all the oil out?

Fred 25:40

From lining, from anything. From drilling, yeah, doing whatever. So it’s just sort of turned into just this joke, basically, a token sort of gesture to say…

And then you have sovereignty, like sovereignty was never ceded, so when the British first came, in the law books of the empire at the time, even to now, it says when the English were going to new lands, if you went to a new land, if it was gonna be colonised, there had to be some sort of two way…

Amanda 26:12

Someone had to throw down their sword.

Fred 26:13

Yeah. And so, in Australia, what was interesting about Australia, and this is why I feel like it was a really dirty, underhanded thing to do, learning best what worked the best, and then this is the last colonised place in the planet by England… By the time they got here, it was like okay, we’re just gonna say it’s terra nullius. No one was here.

Sovereignty was never ceded, there was no official, and I hear it on the news all the time, they talk about the sovereignty of the government, the sovereignty of the Australian government. You can look it up in the UN, go to the UN and read through all the documents, sovereignty was never ceded, Aboriginal people as a whole group of people, maybe one, and even that is contested, they didn’t speak Englsih, so how the fuck are they gonna… People have popped up and said, we’ve got this…

Amanda 27:04

In order for something to be terra nullius, this land is just empty, blank slate. And yet, there are all these beings on it. It speaks to the complete dehumanisation.

Fred 27:17

Yeah. 1967, my mum was born in 1952, 1967 she became a human being. 1967 was the referendum for Aboriginal people to be counted in the census as human beings. We were counted as flora and fauna before then.

To find my grandfather, where he was born, mum was looking up birth certificates, he was on a cattle register. Just a first name. On the cattle station register, as cattle. Livestock, sorry. That’s in my mother’s lifetime.

Sometimes it just gets a little much in Australia when people are like, just get over it! Like, no. You can’t. There’s no getting over my mum is about to get a payout from the federal government for stolen wages. So up until the 80s, Aboriginal people were having two thirds of their wages, working in mainstream jobs, with everybody else, getting two thirds of their wages taken, and set aside in a special fund for Aboriginals, which ended up being used on public works, so main roads, were all built off this money.

Amanda 28:28

Basic tax.

Fred 28:29

Yeah. And so, the government have just been now, they’re not paying back the full amount, but they’re paying back.

Amanda 28:35

When you look at this stuff, and you talk about those Australians who say just get over it, we’ve moved on, where do you see music, whether it is indie rock, or hip hop stuff, or the desire to carry on super old school traditional music, how do you see that it has broken through to people in a way that maybe just sitting around and talking hasn’t, or going to an activist meeting in a town hall or something, or just reading a book, or just reading an article in the newspaper?

Do you think music has helped people get any of this?

Fred 29:16

Yeah. I feel like it has. And the reason it has is because, as human beings, the core of our being, since the beginning of time, has always been some kind of music. Our oldest songs in Australia, the old songs, are all… your mother’s heartbeat, all the rhythms are like this. As human beings, we feel that music has that power to move you, you don’t even have to understand what the fuck somebody’s saying, but you can feel it, you know what it is. You innately already know what it is. Especially when it comes to traditional types of music around the world.

I can sit and listen to classical music. You can feel what the composer was, the heartbreak that they were going through, or whatever’s being conveyed in that music, and so that’s what I feel today, music, and the performing arts, but music particularly, has the power to transcend language, or politics. Anything like that. It breaks down all barriers. I’ve toured around the world, and I’ve seen it. People come up crying, having people translate, saying, I don’t know what you were saying, what you guys were saying, but I could feel it. I felt it.

Amanda 30:37

Can you explain for someone who’s never heard the words, or has never come across the concept, what the dreaming is?

Fred 30:43

Dreaming is like the closest English word to describe what First Nations, what Aboriginal First Nations people here in Australia, the closest thing I can think of is chi, the life force, is like the dreaming. The dreaming was there in the beginning, it’s every section up until now, and it’ll be here when we’re gone, and we’re all a part of it. But what’s interesting is, with the songs in particular, their descriptive verses on sections of the dreaming, sections of that echo in time, from different parts of it, that were handed down from generation to generation, to explain what was happening in a time and a place throughout history.

Amanda 31:31

Can you explain song lines too?

Fred 31:35

So there’s song, so I’ve got songs, some are public songs, and just songs that are connected to certain areas. But a song line will stretch across a massive expanse of country, and explain every single detail of every single mountain, every single river, every creek, how it was created, what animals, what creatures were there, there are witnesses within the song line, throughout the echo of that happening, so it’s like when you’re singing too, it’s all a part of it, it’s like an echo. So if you stand on the edge of a mountain, and you go ‘coo-ee’ and you hear it go ‘coo-ee’, you can’t see it, but you can hear it. You know it’s there.

Each one of us is a step in that echo, each one of us is one of those echoes in time, so echoing that old voice of those old people, and it’s coming through, carrying that same story about different animals witnessing the creation happen, and then the being that’s creating things, that character, there’s characters in it.

Amanda 32:42

So can a song line be performed, and does it have a beginning and an end?

Fred 32:48

It does, it has a beginning and end, and in terms of me talking about it, I’m 41, and still what I can talk about is just the tip of the iceberg. There’s an iceberg, there’s the tip, and then it goes down, and that knowledge is held by high up old people.

Amanda 33:05

Can you sit down with someone, and play them a song line, and…

Fred 33:11

It’d take a long time. There’s one for my clan, it’s 300 verses.

Amanda 33:17

How long would it take to deliver?

Fred 33:19

Months.

I was talking to somebody, my big brother, I was talking to him about it, and I said, it’s just heavy lifting, it’s like the most mentally taxing thing you can do, that you choose to do, and when you start it, you just can’t stop. You have to complete it.

Amanda 33:44

So when I was up in Darwin, I was in the local history museum, the art museum, and I found this book that’s clearly just local, it’s not a book you can find on Amazon, just local printer, teeny weeny book, called White Fella Culture. And it’s a handbook on how to understand how, and why, white people are behaving in these really difficult to understand ways.

And then also really interesting, at the end, flip side, this is the 7th edition of the book, there’s a bunch of stuff that white people just do not understand about Aboriginal culture, we all have to live here together, we all have to work here together. And it was so interesting to see, this is a basic handbook. This isn’t some woke activist, this is just basics, like you have to do a job together, you don’t understand each other’s cultures, you don’t understand each other’s etiquette.

And one of the most fascinating things I came across, especially cos of what interests me, was about asling. What you’re allowed to ask of another person, according to this brochure, in white fella culture, versus black fella culture, Aboriginal culture. What have you seen, just in terms of oh, this is just a giant misunderstanding, in terms of the way white people ask for things, and then what they expect, and how they expect it all to go, versus the way indigenous people…

Fred 35:11

I was talking about this just yesterday, actually, saying, there’s a whole thing around, it’s like extraction, I feel like it’s more, even when it comes down to linguistics, there’s an extraction, and the big thing that is disturbing to a lot of Aboriginal people in anthropology, so it’s just this mass extraction of information. That sort of comes through in… not all the time, but there’s an extraction of oh, that’s not a reciprocal thing that happens.

Amanda 35:48

So when you say anthropology, you mean people just coming in, looking at this culture, sterile academia, just I want this knowledge, I want these facts.

Fred 35:58

I want the knowledge, but not to just have a conversation, like we’re having, but it’s like, I want the knowledge, but I need it in this scientific way, set out like this, I’m recording you, start talking now, bang. Okay, wait. And then it’s totally, it needs to fit a scientific practice that’s been happening for a hundred years, that’s out of date, and out of fashion, and out of style, everything, but everything has to fit within that context, whereas there’s no conversation, there’s no talking.

Amanda 36:32

Well, there’s no humanity.

Fred 36:33

There’s no humanity in it! Yeah, the humanity’s sort of removed. But then there’s like, with asking, we’ve got this thing where, I don’t notice it all the time, and I’ll notice I have to translate it sometimes, cos I have cousins and they’ll say, if I’ve got a non-indigenous mate, he’ll go, oh man, can I get a lift, I’m going to… and people will say oh okay, no I can’t, I’m going the opposite way. But black fellas won’t ask you the question directly, they’ll go, oh… Where are you going to after this? You got a car? Oh yeah, yeah. Elicit a response.

Amanda 37:06

An invitation.

Fred 37:07

An invitation.

Amanda 37:08

You invite an invitation.

Fred 37:08

To then say, oh, well where are you going? Oh, okay, well I can give you a lift. And so, I’ve seen it happen a million times, where just mob, communion mob, from anywhere in the country, will be like, where are you going, which way are you going after this, where are you heading? And that’s the question, and so if I’ve got a non-indigenous mate, they’ll be like, oh yeah, I’m just going home. I’m like no, no, brother man’s asking where you’re going, and if you’re going the same way, he wants a lift. Like, oh, okay.

Amanda 37:42

Yeah, and so it’s really handy to have a translator. I mean, I have definitely, as an American married to a British person, they have a lot of the same rules. British people, they will invite you to invite them by skirting around a subject. I go through this with Neil all the time. His thing is like, so darling, are you a bit hungry? Are you hungry? And I’m like no, I’m good. Anyway… And he’s just sitting there going like, but she’s supposed to ask me if I’m hungry and then offer food, and I’m like, yeah. Where I’m from you’re just like, hey, I’m hungry, can we go eat? And yeah, that’s not, they’re not allowed to do that. Just not allowed.

When you get two sets of etiquette, and you are trying to get shit done, it can be very difficult.

Fred 38:31

And what I find in Australia, which is really unusual, black fellas have to learn, from when you’re born you have to learn English. You have to learn how to operate in two totally different worlds. Non-indigenous people in Australia, I don’t need to know about their fucking world, that’s over there. I’m just gonna do what I do. Oh wow, that happened?! It’s like, come on, read a fucking book. Go to the library, read a fucking book, it’s history, it’s recent history, this shit is here, it’s not just popped up out of nowhere, shit happened, shit’s happening now, it’s gone on.

So you can opt in or opt out. Whereas Aboriginal people, we have to learn… my mum, when I was little, can I teach you this now? What’s that? Betty Botter bought some butter, but she said the butter’s butter, if I put it in my batter it will make my batter bitter. But a bit of better butter made Betty’s batter better. All these things about diction and all this, I said, what? And I remember thinking, why are we doing this? She said, one day, you’re gonna have to go out into that world there, and you gotta speak their language, you can’t be walking around going ahh, yeah, what you doing my brother, which way, eh, oh yeah, you can’t talk like that. You’ve gotta talk, there’s a linguistical term for it, when I go to hang out with my cousins…

Amanda 39:50

Code-switching.

Fred 39:51

Code-switching, yeah! Just code-switch, totally.

Amanda 39:54

You’ve toured Europe and the US.

Fred 39:59

I’ve holidayed in Europe, but I’ve toured the US.

Amanda 40:01

Well, you’ve been there. You’ve soaked it up. So, do you feel a difference in the way Australians are dealing with this kind of stuff, dealing with history, dealing with genocide, dealing with what they’re being confronted with?

Fred 40:17

In Australia, it’s weird. If you go to Germany, there’s shrines, it’s talked about, it’s taught in schools. The Holocaust happened. It was a thing. It happened, it was real, it happened, it’s there. There’s no escaping it. And then how do they move forward as a country? Educate their next generation, so that shit never happens again. That’s the narrative that’s happening there.

In Australia, it’s like, it just sort of doesn’t get a mention, it’s just sort of like nah, just leave that over there, don’t worry about it. It’s Australia Day, man, it’s not Invasion Day!

I wrote a poem once, the lights are on but nobody’s home. It’s too close to home, it’s too…

Amanda 41:09

Well do you wonder if that has to do with the fact that Germany got its ass kicked in the war, and then most of the Jewish population, there was almost a return to, well we can go back to the way things were before this whole insane thing happened, and this Jewish community can still live here, or they’re gonna head over there. And here, it almost seems like to completely reckon with what happened, there might just be too much to lose. What’s the way out? How do we fix this? And since we don’t think we can, it’s just too confusing to talk about.

Fred 41:47

Yep. We’ve got like, third world conditions in a first world country, just five hours away. For instance, with our mob, Butchulla mob, Fraser Island, K’gari, it’s the biggest… It gets the most income of any national park in the whole country. Millions upon millions of dollars. The community just said, we have native title over the island. If you gave us 2% of that, our community would be flourishing. 2% of those millions.

Amanda 42:18

Those millions that usually go towards what?

Fred 42:21

It just goes into the economy. Or non-indigenous businesses. So as a native title holder, it means fuck all. You can’t have economic gain, on your own country. So there’s all non-indigenous tourist companies running. We’re not allowed to have one. We can’t bottle the water, we can’t do anything. But the government can allow a mining company to come, and just mine the fuck out of it. They can’t on the island, because it’s protected, like world heritage protected. And saying that, the cultural heritage act around the country is a joke. They use that to protect sacred sites, but you can lay a map of cultural heritage sites, and mine sites, over each other, overlay them, and it hasn’t protected anything.

Amanda 43:02

So, we were just at the same music conference, and speaking of music and art, trying to wrangle its way into this conversation, make any kind of attempt at progress, how do you see artists, especially when white people come up to you and are like, how can I be a good ally? Especially when things are feeling a little hopeless, what can you say to them?

Fred 43:25

One is like, just educating yourself on the history of the place. Even the history of the community where you live. Pardon me, there’s like, just around the country, every major city and major little town has a Boundary Street or a Boundary Road. And if you look at the map, it goes round the whole city. And after dark, if you’re black, you’re getting hung or shot, and that’s the reality of it, and so that’s never talked about. So one thing is education.

But then when it’s time for action, it’s just like, pass the mic. Give it to someone who can speak from an authoritative viewpoint on it, and give them the voice. Don’t assume you can be that voice, people need to be empowered to have a voice, because for far too long we just haven’t, we’ve just never, we haven’t had autonomy, or the power to have a voice. It’s always just been controlled. Controlled, but then, because it’s been controlled by government, then they’ll sit there and pick it apart. Oh, it doesn’t work, you guys are the problem, you’re the Aboriginal problem, it’s a problem, it’s a problem, every news report, what are we gonna do about Aboriginal communities, they’re just out of control, it’s this, it’s that, it’s like… You’ve got the strings, you’ve got the power.

Even with mining companies going into the communities, some communities are getting royalties, but those royalties, and the jobs that they’re getting, are shit-kicker jobs in the mine. Nobody’s getting a university education out of it, or working their way up as an executive in a mining company. All the mining money is going, all the workers are flying in and flying out, the community get royalty cheques. There’s programmes and stuff that money gets funneled into. And in some communities, people might get a royalty cheque. Some communities have the skills to know what to do with the money, others don’t. And we share, so if I’ve got something, and somebody asks me, I’m fucking giving it to them. If I’ve got $50 in my pocket, and they ask me for $30, yeah, okay, here you go, and that’s our responsibilities to family, to make sure that other family… But that concept doesn’t work in the western structure, in today’s… So if somebody’s getting their royalties or whatever, everybody that they’re connected to, even if it’s a neighbour, and the neighbour’s not connected to that tribal group, the neighbour’s getting fed.

Amanda 45:59

It’s a generosity-driven system, as opposed to a I’ve got mine-driven system.

Fred 46:07

Yeah, but then it’s looked at as a backwards system. It’s like, no, it’s not backwards. The thing that is dysfunctional about it is all stuff that was introduced to the culture, not what is the breadth and depth of the culture, and everything that it represents, the realness of it. It’s all the imposed stuff that government sort of picks apart as oh, that’s your culture, it’s like, no, that’s imposed, that’s all imposed, it’s stuff that was imposed on us, we’re not…

Amanda 46:38

So with Australia sort of back in global headlines right now because of the bushfires, where do you see the connection between this breakdown that we’re talking about, and the country being on fire?

Fred 46:51

A prime example is the recording you just put together, the Firesticks Alliance has been there for a year. There’s not even a mention of it, of this organisation, in any mainstream media whatsoever. Talking to the fire chief, and the fire chief’s like…

Amanda 47:09

And for people who don’t know what Firesticks is, to explain what it is…

Fred 47:12

Yeah, Firesticks is an organisation of Aboriginal people that use traditional burning methods on the country that have been used for thousands of years, to keep from there ever being the magnitude of bushfire that we’ve had in the country now, and then when we had Black Friday. And because that traditional knowledge is there, and that has been shared around different communities, but it’s not getting federal government funding, it’s been totally ignored.

Amanda 47:43

And do you think that’s just pride?

Fred 47:44

It’s pride thing, cos we’re not gonna acknowledge that, you’re not gonna acknowledge your connection to one place, for 4,000-plus generations, 65,000-plus years, we’re not gonna acknowledge that. What we will acknowledge is ah, you know, you’ve got some kids who sniff petrol every now and again, and we’ll acknowledge all the dysfunctional shit, and we’ll make sure we slap that on the front page, and they won’t acknowledge… It’s bizarre. Because it’ll save the government so much money, but even…

It’s crazy, cos I was watching the news, and just the other day, they were talking about, we’ve now had all this rain, so now we’ve gotta work out, how do we get all the cattle and the animals that are being farmed, there’s a book called Dark Emu, and in the book it talks about any native animal in Australia doesn’t have hard hooves, it has soft, padded feet for a reason. They’ve adapted. And so they’re made to integrate with the land, in a way that’s not compacting soil and things like that, whereas that’s happening. And so the talk is, the bushfires are slowing down, we’re getting rain, and now people are still talking about oh, we’ve gotta re-boost our stock and all this stuff, and it’s like, are you that crazy? Just insane?

Amanda 49:13

That’s how it felt after 9/11 in New York. When the overarching narrative wasn’t, how did this happen, and how can we keep this from happening again, but it was like, the most important thing right now is go to the mall and spend money. Get the economy back up! Wrong reaction. You’re not getting the right lesson out of this punch in the face.

What are a couple of things you’re seeing right now that are actually giving you some hope?

Fred 49:38

I feel like it was a bit of a wake up call for some sections of Australia to go, you know what? There was a non-indigenous… no, I don’t know if it was non-indigenous, I think his wife was non-indigenous, he’s an indigenous elder in a community, but they own a whole bunch of acreage. The bushfires happen. They’d just had the Firesticks Alliance guys through, the season before, two seasons before, to do some traditional cool-burning they call it, coal-burning, cool-burning. Literally, their property didn’t get touched. And their neighbours, and surrounding areas got touched, and I think that was a bit of an eye-opener for people to say, hey, you know, there is this traditional knowledge, and it’s not knowledge, it’s a science. There’s a science to it, it’s not just gobbledegook that somebody’s made up. That’s sort of opening the eyes of the country.

Music, in terms of music, indigenous music in Australia is getting bigger, and more widely accepted, and the stories, and the narratives that are being played out by musicians where there’s hip hop, or folk, or whatever, rock. I feel like in the last 10 years, 10, 15 years, there’s been a… especially with that word you were saying earlier, woke, especially with people being woke to exactly what is happening, and being able to… I think people are educated, slowly becoming more educated about, especially now in the here and now, where it’s the cult of the individual, everybody’s just about me, and there’s no one else, and I’m gonna get famous, I’m gonna be an Instagram influencer, I’m just gonna do this. But I feel like there’s, not to that extent, but certainly to more of an extent than there has been in past years, there’s this community of people, and a generation of younger people coming up now, that are hungry for what they’re not being taught in school. They’re hungry to learn, and find out…

Amanda 51:44

They’re curious.

Fred 51:45

All the information that’s being held from them, or not being… Yeah, they’re curious about it. Approaching life with this thirst for knowledge of what it is to just be a human being, and exist, and other people’s stories of being a human being that exist. So I feel like that’s an awesome light at the end of the tunnel in what sometimes feels like a bit of an apocalyptic thing.

But it’s like, it’s not all doom and gloom. There’s cool stuff happening.

Amanda 52:14

You brought something. Will you play for us?

Fred 52:17

Yes! We call this djaju. Don’t worry if you get the pronunciation wrong, cos I won’t judge you! But a djaju, it just means stick. It’s what we call a boomerang that doesn’t come back.

(Fred sings in his native tongue)

I just said hello, women and men, boys and girls, anybody that’s listening, the language that I’m speaking in, that’s my grandmother’s language, Butchulla. Today, right now, I’m gonna sing you some songs in my grandmother’s language. It just means look, listen, learn. That’s the closest translation.

So if you ever get the chance to visit sunny Queensland, there’s a place called Harvey Bay. There’s a suburb in Harvey Bay called Urangan. Urangan mate, Urangan. And the proper way to say Urangan is Urangan. And Urangan is the sea cow, they call it the sea cow. And so this song is an old song, it was recorded in 1949, by old Cobo Williams. It’s one of the last old initiated men from my tribe there now, Butchulla. It’s a song of how the urangan migrates, and what happens when it comes up the east coast, like what we do. Sorry any vegans that are listening, but we taste it with a spear, and there’s a tip on the spear, and the spear comes off into the animal, and then you basically on a canoe, and you follow it around until it’s worn out, and then you can drag it in. And then everybody’s eating for a month.

This is a story about that, and the process of it. Ganay is a spear, and ganay-du is when you shake the spear and you let it go. And then the second part of the song is about the men doing that, and the women collecting the yams, and getting ready for the men to bring back the meat, so that we can have a feast. The story is an old story, and every different Aboriginal group around the country would have a separate section of that story.

(Fred sings in his native tongue)

And it goes on and on and on, and just repeating, it’s like a meditative thing.

Amanda 56:14

Can you translate some of the words?

Fred 56:17

Yeah, so ganay is a long spear for urangan hunting. Ganaydo is when you’re shaking it, rattling it, getting ready to let it go. And then (Aboriginal phrase) is saying the women collect the yams, and they’re getting ready for everybody to come together for a feast. And so there’s that.

There’s a whole bunch of different stories, and different levels, and places where you can and can’t give that information, freely give that information out, even within the context of family, or tribal situations. And there’s stuff that, when I go up to Harvey Bay, Butchulla country, I’ll go visit my brother, and the other Butchulla songmen, we’ll sit down, and we’ll sit down for two hours, and sing songs that each one of us has learned, and been given, and some of them that we all know, and have been given collectively, and just remember those old people that passed on that information, and the older big brothers that gave us that information.

But then, every generation, when you’re singing, they’ll say, it’s not you singing. I was talking about that echo, it’s not you singing, it’s the soul and the collective memory passed down from generation to generation to generation. And that’s what hits people, when we all look in the mirror, these eyes don’t belong to us, they’re not ours, they belong to somebody… somebody who had to dodge a wooly mammoth. Somebody had to survive epic changes in climate over thousands and thousands of years, for us to just even be sitting here in the studio, as individuals. So when you think about that, and then the collective memory, and that passing down of that knowledge, and then the essence of that being, and knowing that they’re there with you, and when you sing, they come out, and they’re here for that moment in time, and then they go back.

Amanda 58:22

As a musician, do you feel physically different when you’re playing that stuff versus when you’re freestyling, or creating something new?

Fred 58:32

There’s times when I can be doing a folk song, and that same feeling comes across, or listening to music, listening to people, and you can tell straight away, you’re like ooh, your hair stands up, it’s coming from another place. We’re each here, but we each represent, what we all individually represent, is generations and generations and generations of people that have passed it on from the beginning of time. Music has always been there.

Amanda 59:03

When I met you at Woodford Folk Festival, I had just seen Archie Roach talking about his new book, which I picked up and started reading, and it’s incredible, an entire generation plus of indigenous Australians, just forcibly taken out of their communities and given over to white people, and adopted. And Archie grew up that way, and then became a really powerful songwriter, storyteller.

And I asked him, which vessel do you pick? If you make all sorts of different kinds of stuff, and you are a storyteller, and you’re into traditional music, and you play guitar, and you can conduct a children’s choir, and, and, and, like, what do you feel about the choices you make about which vessel is gonna carry on which story? And he said something really beautiful about how, when we’re all gone, and the big we’re all gone, there are no more people, he said something to the effect of, these stories aren’t gonna die. Almost the vessel doesn’t matter, because as long as you put forth the effort to carry the message on, no matter what the package is, whether it’s hip hop or clap-sticks or guitar or fucking insane avant garde modern dance, it’s lamost like the intention to carry the story forward carries the story forward.

You and I met at this festival, and then it’s very possible I would have never seen you again, but then I needed a didge player for this Bushfire record. I called you, and you really graciously just said yes. What was your context for this song? I, as an American, had literally never heard the music or the lyrics or the title of the song Solid Rock until a month and a half ago. Because I’m American, it’s not part of our lineage. And everyone who I told that to in Australia, was like, dumfounded, jaws on floor, how could you not know this iconic, anthemic song? I mean, there you go. I didn’t know cos I didn’t know. I came to find out really quickly how much this song meant to so many Australians, but what can you tell me about the song, what it meant, if it meant anything, maybe what it didn’t mean? Anything about this song that can give some context.

Actually, let’s listen to a second of it, just so people can get some context.

MUSIC – Solid Rock by Goanna

Well they were standing on the shore one day

Saw the white sails in the sun

Wasn’t long before they felt the sting

White man, white law, white gun

Don’t tell me that it’s justified

Cos somewhere someone lied

Amanda 61:53

This would have been, I think, 1983, 1984, when a band of definitely all white people, Goanna, singing this song that they’ve penned about indigenous rights. What did the song mean to you?

Fred 62:04

Yeah, when I was growing up, if it came on the radio, or somebody had the tape, and then eventually the CD, we’re pumping it, we’re just like yeah, solid rock! And it’s an anthem, and we were like, yeah, man. This is somebody, not from our community, that’s talking about our plight in a song! In this anthem, which is essentially a protest song!

Then, when I got older, I had the opportunity to play didge on that song with Shane Howard a couple of times. I was talking to him about it a few years back, up in Bourke, so I call him Bawanya, which means big brother. And the reason I call him big brother, crazy, and it’s… so when you said, come play didge on this song, it’s called Solid Rock, I was like, yes!

So the significance of my connection with this fella is, when Shane Howard and that song, is when the song went big in the 80s, and they toured, it went off, but it turned into this pub anthem, and so everybody was singing it, didn’t really understand the context of it, and were using it in the wrong way, to be like, fuck yeah, this is an Australian anthem, man! Solid rock! Living on…! And so, the uncomfortable bits in the story of the song sort of got skirted over, skimmed over. And Shane lost his shit not long after, and was like, fuck this. And he told me, word of mouth, I’m gonna tell you a story here real quick. So he was really disheartened that it got picked up, and used in the way that it was used, and went, okay, I’m going bush. And he went bush, up to the gulf.

Amanda 63:55

What does it mean to go bush, for the outsiders?

Fred 63:58

He went off…

Amanda 64:00

Off grid.

Fred 64:01

Off grid, for several years, and lived up with all my family and mob up in the bush. So they gave him my skin name, Bulanyi, and because he’s older than me, I call him Bawanya, big brother. And so, he was like, disheartened with it all, went bush. Went and lived with the community, and they took him through certain things, and he became a part of that community up in the gulf of Carpentaria, so he still has that connection to this day. I was up visiting my auntie, my Gowija, it’s like your mother’s sister, Biligi is a kinship term, Biligi is the eldest sister. And she’s really cool. And somebody said ah, gee, if anybody had Shane’s number… I was like, yeah, I’ve got his number! Don’t put it on! And my auntie, she just… ah, hey my boy! He’s like, hello auntie April!

And then they started singing a song together, she sang him this song when he was, back in the 80s and 90s or something, then she’d always sing it to him, and then he started singing that song, and then she’s crying, and she’s singing it, and he’s crying, he said ah, I wish I could be up there. And it was just this nice little connection with family, cos he’s family now. It’s not anything other but family. He’s connected, and he’ll always be connected.

So then, when you mentioned it was that song, I was like… I’ll be there.

Amanda 65:42

That’s so amazing. It’s such a teeny, beautiful, weird world.

Fred 65:48

Yeah.

Amanda 65:49

This has been the Art of Asking Everything podcast. Thanks so much to my guest, Fred Leone, and also to Jordan Verzar for introducing me to Fred.

You can find Fred’s music on Spotify, YouTube, and also we are putting together a companion Spotify playlist for this podcast, so watch out for that.

The engineer for this interview was Nick Edin, for all the music you heard in this episode, you can go to the new and improved amandapalmer.net/podcast

The podcast was produced by FannieCo.

And lots of thanks to my incredible team, who are in the middle of taking some very, very, very, very deserved time off. Hayley Rosenblum, who makes so many things possible, she’s the ghost in the machine of our Patreon, and she makes sure everything gets done, words and pictures and live chats. She worked her ass off in the run-up to this time off, putting together so many things, including the posts with all of the photos and the footage, so thank you Hayley.

My assistant, Michael McComiskey, who makes sure that everything gets scheduled, and that emails do not go missing. Thank you, Michael.

My Merch Quene, Alex Knight, in teh UK, who’s also helping transcribe all of these conversations so they’re accessible to everyone, thank you Alex.

And we welcome in a new team member, Kelly Welles is helping me do a lot of the social media posts, and is also helping with some editorial, thank you Kelly.

And of course, my manager Jordan Verzar, who brings it all together.

And last but not least, and very importantly, this whole podcast would not be possible without patronage. Right now, we’ve got about 14,000 people making it possible for this podcast to have no ads, no sponsors, no censorship, no bullshit. Just the media, doing what we wanna do. So many thanks to my high level patrons: Simon Oliver, Saint Alexander, Birdie Black, Ruth Ann Harnisch, Leela Cosgrove, and Robert W. Perkins. Thank you for your generosity, and for helping me make all the things.

Everyone else, please, if you’re not supporting the Patreon, I cannot tell you how much it means to me to be able to work with that kind of sustained support. So even if you can only give a dollar a month, go become a supporting member. That also will just mean that the podcast lands in your inbox when it comes out, along with the posts and all the background blogging that I do. It is coming out every Tuesday, and we’re gonna keep going with that as long as my team can manage.

And I just wanna thank everyone who has been rating the podcast, and spreading the news, and sharing the episodes. It means the world to me. I don’t have a big promotional company, I don’t have a huge team going out and advertising this podcast, it’s just word of mouth, so thank you to everyone who’s been rating, reviewing, sharing, and doing all of that good stuff.

I’ll see you soon. I love you. Signing off, this is Amanda Fucking Palmer. Keep on asking everything.