Dear Robert Smith (an open letter)

Here is a picture of a piece of paper i decorated in 1988. It’s been living in a shoebox and has survived five moves:

Dear Robert Smith,

The weirdest thing about writing you this letter is the constant temptation I’m feeling to use words I’ve read thousands of times from my own fans, written on all variety of international stationary and ripped-off spiral-bound school-notebook paper: “I know you’re busy. You must get lots of letters like this. You must hear this all the time….”

And should you never happen to read this (and it’s really fucking long), that’s ok. I am writing it for me as much as for you.

And I’m also writing it for my own fans, because I think they’ll relate to what I’m going to say and I think it might help them to understand me.

****

(audio cue: for those of you if you really ARE going to read this long fucking letter, I suggest you throw an old favorite record on for good measure. it might help. i suggest a cure record. or something sad. i’ll wait. ok, now read.)

****

So. I saw you play last night at the Coachella festival outside LA.

I played the day before on a different stage, and I’ve just finished a really long and grueling and pretty fucking wonderful world tour promoting my own new record which came out in the fall (and it’s called Who Killed Amanda Palmer and I think you’d really like it). Coachella was basically the last stop before I take my first true break from touring in a long, long looooooooong time. I’ve been traveling endlessly and brutally with The Dresden Dolls – and now solo – for the better part of eight years.

And I’ve gotten a little lost.

Last night, you helped find me.

I need to explain. And I need to thank you, and also…I owe you an apology.

Last night, before you took stage, I was feeling exhausted but happy. I hate festivals, usually. I’ve been touring too long to think that I could actually enjoy attending one. But this time was different. When I saw the Coachella line-up and saw that it included The Cure and Leonard Cohen and My Bloody Valentine, I decided to turn the weekend into a vacation, instead of coming straight home to Boston.

So I played Saturday (my set, by the way, was magnificent and I crowd-surfed to Wagner) and by Sunday I was feeling the weight of the year since the release of my own album lifting off my shoulders. I found friends here and there in the festival mess and actually sort of starting enjoying myself. I hadn’t thought much about what the experience of seeing The Cure might be like. had simply planned it out months before in my off-handed responsible-adult kind of way: “hm….need to book flight to coachella, must check festival line-up, hmm, leonard cohen and the cure are playing, their music changed my life once, long ago….quick note to adult self, should see them play, might have some sort of awesome nostalgic experience, leave time in schedule for that possibility.”

I don’t GET excited anymore. Not like I used to. I wasn’t even thinking about what to expect from you.

I just knew I should be there.

My Bloody Valentine played right before you and I hadn’t known what to expect of them, either. I was alone, and the sun had just set, the cold was coming in over the desert and the palm trees were illuminated and beautiful. I’d ditched my crew and was enjoying the feeling of being solitary and anonymous, two drinks in my system, exhausted from my own shows, finding a comfy little spot not too far from the main stage to savor whatever it was that My Bloody Valentine would dish out.

I hate this: but I barely enjoy watching bands anymore, at festivals or anywhere really. I’m kind of burnt. After so many years of touring, you can probably relate. It starts to blur. Bands playing on stage start to resemble ants building hills. Kind of cool….but very practical. The magic starts to wear off after you realize that they’re up there WORKING, day after day.

But…I’d really, really loved My Bloody Valentine in high school.

They’d been a mysterious and sex-charged sonic force given to me on a 90-minute tape by one of my first loves, a boy named Stu. I wore that tape out…”Loveless” on one side, “Isn’t Anything” on the other. I’d never heard music like it before and I’ve never heard anything like it since – they created something completely unique and perfect. It was my summer soundtrack after tenth grade, along with a Velvet Underground (VU) and a They Might Be Giants (Flood) tape. It was the music that lived in my head for that week of the parentally-forbidden boat excursion to nantucket island where Stu was working a summer job as a short-order cook and where I had my first escape from my little suburban town life, having the kind of sex where you understand for the first time what everyone’s been talking about….the real, loving, deep, pleasurable, flickery-afternoon-light-streaming-onto-a-futon-filled-with-sand-from-the-beach kind of sex. My Bloody Valentine played all that weekend and all that year, keeping me feeling special, fillin gmy ears daily with their mostly-impossible-to-understand-lyrics. I never knew what any of the band members looked like (since the tapes had no artwork) and knew nothing about the history of the band (since there was no internet). I never thought in a million years I’d see them live.

Their set mesmerized me (what perfectly controlled grace, what unapologetic and passionate love-noise) and my heart started breaking open a little bit as I felt the reality of my long tour starting to end and the reflections and refractions of what I’d done – and what I was doing with music, with my life, with my fans – flooded into my brain. At exactly the moment I was struck dumb with the combination of pure guitar noise and the crashing realization all my own teenage fantasies really had come true (was I really playing at a festival with some of my favorite bands from high school? My Bloody Valentine, The Cure, Leonard Cohen? Pinch self….yes, I was, oh my god….I was, I really was…. GOD DAMMIT) a fan spotted me in the blaring noise, tapped me on the shoulder and held up her phone, onto which she’d written a text message: “I love you so much I can’t even speak. Will you take a picture with me?”

I hugged that girl for dear life. She probably had no idea why I was crying so hard.

While she stood next to me, and we watched these serene noise-gods on stage playing to a rapt crowd, I let myself go and allowed myself to lose it. Put my hands in the air and closed my eyes and tried to put the music inside me. Towards the end of their set, they built and sustained a wall of shimmery sonic assault for about twenty minutes, the whole band barely moving on stage, just gracefully and subtly plucking miniature millimeters of guitar string that flowed through pedals, amps, wires and speaker cones to be transformed turned into crashing towers of decibels and lightyear piles of psychedelic raw sound radiating for miles into the cracked flat desert night. I swear to god, I’d only had two gin and tonics at that point. I hadn’t taken ANY acid or ANYTHING.

My Bloody Valentine finished and I walked like a zombie, tears still streaking down my face, past the crowd, feeling dazed. I went back to the VIP tent, sank another gin and tonic. Then headed back out for your set. I clambered through the crowd and got a decent spot in the front left section, about 100 feet from the stage. And I waited.

I braced myself. Funny, I hadn’t been expecting to feel like this. I was nervous. I was afraid, sort of.

I waited for you.

You…

You were my whole world for so many years of excruciating teenager-ness. From the first tapes I copied from my step-brothers ultra-cool tape collection, you had me. The rest of his collection (The Cocteau Twins, The Clash, The Replacements) well…I liked it all well enough, but it didn’t speak to me. Not the way you did. There was something so honest, so painfully honest and real, about your words and your delivery. I desperately needed someone to believe. Someone who was telling the truth. As far as I could tell, nobody else was. The teachers and family around me were stupid, lame suburban pod-people, allowing themselves to be spoonfed the cultural koolaid. I was fourteen, I was an opinionated little twit, I wanted to feel and to scream, I needed allies, comrades, back-up, and I was pissed that I couldn’t find any.

Mostly, I just needed a favorite band. Didn’t everybody? I needed a home that was Mine, a t-shirt I could wear that would serve as a constant reminder to the rest of the eight-graders – all of whom, in my snot-nosed way, I considered irretrievably lost and flailing in their own personal suburban circles of fiery hell (aka The Mall) – that I actually did belong somewhere. So I abandoned The Stray Cats (sorry, Brian Setzer) and decided to devote myself soley The Cure. Those first few years of being in love with you were like any honeymoon stage of a relationship. My heart would pound if I flipped through the Cure section at the used record stores in Harvard Square and spotted a piece of vinyl with unfamiliar artwork (sadly, those were often $30 japanese imports that I could never afford and that were too big to effectively shoplift). Your posters were the cornerstones of my bedroom decor: one huge wall-sized poster on each side of my cluttered room, the main shrine above the defunct fireplace devoted to the Boys Don’t Cry poster surrounded by strings of colored christmas lights. They glowed around your silhouetted figure and guitar, and I gazed nightly at your back. You turned away from me, hiding the tears in your eyes, in a truly ground-breaking Sensitive-Man-Stance. I felt certain that I was worshipping at the altar of the correct church.

(the poster is still – thanks mum – up in my old room, i took this picture a few days ago when i was out there eating dinner):

I bought every album, knew every word to every song, I read and re-read JD Salinger and Albert Camus when I found out that you’d referenced them in your lyrics.

I bought every piece of paraphernalia I could find – buttons, patches, 7”-vinyl interviews and shirts (I had a collection of eight, two of which I still keep and treasure and occasionally wear to bed when I need comforting).

I drew pictures of your face and your hair (it was very, very difficult getting your hair right, dude) all over my school binders and on pieces of cardboard that I would add to the growing collage on my wall. I re-painted your album covers on various surfaces. I spent hours in class perfecting the band’s name font as it appeared on “Head on The Door”, working hard to get squiggly criggly letters just right. Once I had mastered this skill I applied it (using all variety of magic marker and fabric paints) to jackets, hats, ripped jeans, the inside of my closet and (occasionally, when I got bored) my forearms. I drew a cartoon for my xeroxed high-school fanzine depicting The Cure in a galactic battle against my nemesis, that most-hateful of bands that represented everything wrong and false: New Kids on the Block. Your band won.

I tried to write songs like you. The THINGS you sang, the way you weren’t afraid to peel yourself open and purge, seeth and cry about the brutal feelings that we ALL HAD but weren’t expressing, that is why I loved you. All other music fell short. You were Real.

I listened to you and thought: THAT. I want to do THAT. Whatever he’s doing. Whatever he’s making me feel….THAT’S what I want to do to people someday.

I didn’t even know what you were talking about half the time, but I knew you were reaching deeper, further, realer than the other records in my collection. In your lyrics, you were shredding people apart for being superficial, for not being authentic. People said the music was gloomy, depressing, over-dramatic. I never heard it that way. I just heard it as honest. I’ve learned from watching thousands of bands over the years: it’s not enough to just ooze pain or complain into a microphone. Lots of bands try to do that and fail miserably. You did it right. You were tricky. You used just enough words, just the right words, always the perfect package…enough melody to draw me in to hold me there and drive the stake of prickly truthfulness through my heart.

And at the end of the day, you write a damn catchy pop tune when you feel like it. And that inspired me so much as a writer…the fact that you could be so passionately agonizing on one track and then turn around bopping and dancing light-heartedly the next. I followed your example and I assumed that everything was up for grabs when it came to songwriting. You made this ok.

I wanted to know things about you. I needed to.

There was no Wikipedia, no Google.

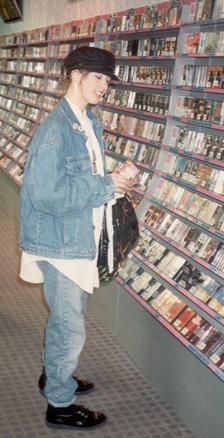

So I read whatever information I could find and where I got this information pre-internet, I don’t know exactly….mostly magazine interviews, I think, the accompanying pictures from which I would clip out and paste to the wall. MTV and 120 minutes would occasionally let information drop, which I would suck up like a sponge. I learned enough to know that somehow I had to save the money for a ticket to Crawley, Sussex, in the United Kingdom, where I would somehow run into you and that you (according to a story in my head that seemed very real at the time) would instantly befriend me. I vagely knew that you were married (happily, according to all counts, and possibly even with children) but this was somehow easy to overlook. Clearly, the minute you met this very intelligent, beautiful and raw open wound named Amanda, you’d probably just leave your wife (who’d understand, of course, and she could even hang out with us…she was British and Your Wife and thus probably pretty hip). And you would most likely ask me to marry you. I would say yes. Tickets to England were expensive. I was frustrated. When my parents informed me that we were going on a family trip to London the spring that I turned fifteen, I was excited MOSTLY because I assumed this would be the trip that would bring us closer together. The closest I actually got to finding you over there was the UK-only pink-cover cassette version of “Three Imaginary Boys” at HMV on oxford street. My sister Alyson took a picture of that moment (note the double denim!!!):

I wasn’t thinking about how or whether any of this would come into focus when I made the plans to see you. As I stood there, packed in with the other bodies at the festival, feeling free, feeling ready for anything, feeling grateful, most of all, that I’d taken the time out of my life to be standing here in this desert at the moment to see my old favorite band play, the cogs started turning. This was what I’d wanted, this was the feeling I’d signed up for. The nostalgia. This was why I’d bought my ticket to spend the extra day here. I wanted to re-live something. Right? I wasn’t sure. I hadn’t really given it any thought. I figured it only made sense given that the closest I’d ever come to having a religious experience was at a Cure concert in 1991.

Oh god, that show….that show that I looked forward to for months and months and months and months. Due to a massive stroke of synchronicity my mother, who had only Rolling Stones and Beatles and Fleetwood Mac and Handel in her record collection, had an ex high-school sweetheart who was driving a truck in your touring crew. She knew nothing about the rock road, but he’d come through town a few years before and hooked us up with Beach Boys tickets. That was my first real concert, I was 12. It was boring. I didn’t really care about the Beach Boys. But a few years later he phoned again and said he was driving for The Cure and she recognized the name…no doubt from seeing it plastered all over her youngest daughter’s bedroom walls, school binders, and (occasionally) forearms. I remember the sheer volume of the scream, on the order of thousands of decibels, that escaped my mouth when I was told that I could not only GO TO THE SHOW, but POSSIBLY GET BACKSTAGE. I ran, making banshee-like sounds, to the phone and called Holly, my best and only friend and fellow Cure-devotee (though not, I was certain, as devoted as I….since she was convinced she was going to marry Johnny Depp from 21 jump street, who was totally not as hot as you). We would go together. I dreamed night after night about how you’d breeze by me in some anonymous backstage hallway, recognize that I was your true love, and possibly make out with me. I knew this was a distinct possibility because by penpal Eve Stoddard had been to a Jane’s Addiction show at a concert at the EXACT same venue, had snuck backstage, run into Perry Farrell randomly and HE had kissed HER. Obviously, this was rock and roll and anything was possible. I plotted and spent countless hours thinking of what I would say to you when we finally met. I barely slept the night before the show.

left: gothy little amanda, right: holly and me.

It was the Disintigration tour, you opened with “Plainsong”.

****

(audio cue, for those listening, please stop reading and throw “plainsong” from “disintigration” into your speakers. if you don’t have it, download it. and you know what? just get all of disintegration if you don’t have it and let it play for the remainder of this letter-reading. why the fuck not? you’ll thank me, it’s one of the best records in the world. sorry, robert, back to your letter.).

****

As the lights went to black and the crowd roared and those first few chimey sounds started to fill the air, I felt my heart racing. I was going to see you.

Really see you. See you in the flesh. Hear you singing, watch your voice make sounds, live, for me, to me. To us.

My senses sharpened. I held my breath.

When that music crashed into place (and what a perfect choice, that one, a perfect set opener, and perfect album opener….and god, just a perfect song: the huge major-chord crash of joyfully celebration with lyrics as dark-light, lush and vast and deep and bittersweet as love itself), when that first giant synthesizer belted it’s long, jagged and beautiful wave forms into my ears and meshed with the smash of cymbals and dazzling of lights….in that moment, my heart exploded. I now knew something I didn’t know before.

I’ve never forgotten that moment.

Tears streamed down my face and I thought THIS, THIS THIS – it was a feeling that I wanted to bottle and eat and never forget and repeat again and again as long as I lived. Every hour I’d spent longing, every doodle on every notebook, every lyric that I’d quietly memorized and wondered about, all the love I felt for you, for everything, it was all trapped up in this one moment. Not belonging, not feeling right, not feeling human, not feeling good enough, all those feelings were crushed away by the music, by these magic sounds, by the sound of your voice. Here, I belonged. Here, life was perfect. I don’t know if my mouth screamed, but my heart did. In pure joy. I don’t remember much else of the set. I was ecstatic.

I brought home a souvenir of that night, an empty envelope that my mother’s truck driver friend gave to me with all of the bands autographs. I still have it, carefully hidden away behind one of your posters in my parents house. I used to take it out every few weeks and just look at it and think: he touched this.

I was 16. Last night, I was 32. I found myself being recognized in the crowd at Coachella, a few people behind me calling out my name…they had seen my set, they were fans of mine. They were happy I was standing there with them. I was happy they were standing there with me. We were excited, The Cure was about to come on.

I looked around to see who was standing near me. I was alone.

I struck up a conversation with the guy next to me, who seemed really nice. It turns out he was a devoted Cure fan named Dereck who had been to 12 or 13 shows. We started talking, but after a few minutes the crowd started to pulse and murmur: the band was coming. I exploded in cheers and screaming. I’d forgotten about this feeling. My enthusiasm was matched by a few around me, but I also felt sort of self-conscious. I was a bit overexcited. As you started playing, so many of my teeange memories and lovers started flooding back. Your face, your hair, your red lips, the sound of your voice were like a portal. Was this what I’d come for? Maybe.

You wound up tainting and nurturing my early loves and relationships, you were there as a thread, as a spectre, as a soundtrack.

There was Peter, the swarthy 18-year old who had a vintage cadillac convertible and worked crew on the summer-stock production of “The Wizard of Oz” that Holly and I both decided to join when we were 14. After I pledged my undying devition to him AND gave him my first (admittedly disastrous) blow-job in the woods near Granny Pond and he never fucking called me back after dropping me back home, I mourned for ages. I spent tearful weeks trying to decide what the proper reaction was to this kind of brutal rejection and heartbreak and I finally settled on mailing him a fountain-pen-written copy of the lyrics from “The Same Deep Water As You”. At the time, it seemed perfect.

(I know now; he wasn’t worthy.)

What the letter said was:

“kiss me goodbye

pushing out before i sleep

can’t you see i try

swimming the same deep water as you is hard

the shallow drowned lose less than we

you breathe the strangest twist

upon your lips

and we shall be together…”

What the letter meant was:

“why did you drive me to the woods and let me to give you my first (admittedly disastrous) blowjob and then pretend I didn’t exist, you dickhead?”

One summer later, there was Ira, the adorably tall boy with the pink mohawk and scratchy stubble and checkered jacket who I admired all summer in Harvard Square and wanted desperately to capture. When we finally got to his house in the woods of Concord (his mom far away somewhere) we entered his room in the dark, and he plugged in the christmas lights that surrounded his favorite band poster, a slightly smaller version of my shrine….it was you. you, with your back turned to us, hiding the tears in your eyes. You kept your back turned while we made out passionately and gave each other head (my blowjob technique had markedly improved by this point) and I was totally ecstatic because HOW RIGHT MUST THIS BE? THERE’S A FUCKING BOYS DONT CRY POSTER ON HIS WALL SURROUNDED BY CHRISTMAS LIGHTS. We were soul mates. Ira called me back. (But not for very long – that one also ended in sad agony).

My first real true love, the one I was with for a long long time…he loved you too. It was part of how we knew. He had a deeper, longer, more grown-up relationship with your music, but it went without saying that our common love of The Cure made us love each other more. You connected us. He called me back for years (and really, lovingly appreciated my now finely-honed blowjob techniques). He still calls me back, 15 years later, even though we’re not together.

My first boyfriend in college, Matt, was a huge fan. We met after he saw me play my first college show and he showed up knocking at my dorm-room door later that night with a lit candle in a Twinkie. He died a little while after that.

One of my better friends and housemates around the same time, Chuck, who was the fattest, smartest person I knew, endeared himself to me forever one night and he didn’t even know it. We were in the common room of our house, a place called Eclectic, watching the episode of South Park where you showed up as a special guest. When Cartman screamed “Disintegration is the best album EVER” at the end of the show as you vanished into the sunset, Chuck started violently punching a couch pillow and screaming “YES!!! YES!!! FUCK YES!!!” at the top of his lungs. I decided then to love him forever. He died a few years later.

I didn’t have many friends, not then. Not normal friends my age. I wanted to. In high school and college I had lots of passing boyfriends and interesting romances, but rarely real friends, pal-types, the ones that stuck.

For a time, I was led astray.

I admit it. I tried to be goth.

I assumed that if goths liked The Cure, they must be My People. I wanted to hang out with people who felt deeply, who worshipped at the altar of emotions and radical truth, like I did. They wore black. So I started wearing black, assuming that I would be waving the proper visual freak flag to let people know how I was aligned. It didn’t really work. I frequented goth clubs. It was a long, slow painful realization but I finally understood that just because these people were dancing to your music (or The Smiths or Depeche Mode) it didn’t mean they would understand me. I spent a lot of time wandering around disoriented in goth clubs in boston, new york, all over germany….sitting at a dark corner table, nursing beers and smoking, waiting for a song I loved to come on so I could dance, alone. I liked dancing. I would close my eyes and forget. I would abandon myself. But I never met anyone I liked or who liked me. In fact, almost nobody talked to me, ever.

This was obviously not working. What was up with these mean and unfriendly fucking goth people??? Weren’t we supposed to be united in our love of emotion, love, pain, joy in the brutally honest? Didn’t they understand? Hadn’t we come here to commune, to find each other? Obviously not. I felt betrayed and duped.

There was a little goth club in Bavaria (where I lived in 1996) that I would religiously attend every tuesday night. I would dress in black, I would dance, and I would pray and hope that some german goth might talk to me and be my friend. There was a boy there with hair like you, so I considered him an ally. One night, I finally got up the never to talk to one of the girls he was with. Later that night he grabbed my head and pulled out a chunk of my hair, which he shoved in my face. “Don’t talk to my girlfriend, or I’ll kill you”, he said. His friends apologized and told me he was drunk. My head hurt for a long time.

I quit goth.

Looking at the crowd around me at Coachella, I realized: there wasn’t a single person in black. Even the people who were obvious fans and knew every song; they were wearing white, gold, pink, blue. What the fuck was this, when did THIS happen? I realized, slowly, that you became huge while I wasn’t looking. In 1989, everyone who listened to you was black-clad. It must have changed. I leaned over and yelled over the music to my new best friend Derek (who was wearing a white and blue button up shirt) “WHERE ARE THE GOTHS? ALL THESE PEOPLE ARE WEARING PINK.”

“GOTHS UP FRONT PROBABLY” he shouted back. “THERE AREN’T THAT MANY OF THEM, ANYMORE.”

I started talking to him more. I couldn’t believe this guy was a cure fan, he looked so COMPLETELY ungoth. I asked him about the lack of keyboards in the set. I was REALLY missing the keyboard lines…they seemed so essential. Sometimes the slack was picked up by a guitar…but mostly, those wonderful shimmery keyboard lines were just MISSING. “WHERE ARE THE KEYBOARDS??” I yelled.

Dereck explained to me that “THEY’VE BEEN TOURING WITHOUT A KEYBOARDISTS FOR A WHILE.” He then proceeded to shout the entire history of the ever-changing band line-up throughout the past ten years. I hand’t know any of this. None of it.

The songs you were singing, they were so beautiful.

Some of them I knew by heart. But some of them, I didn’t know AT ALL.

I found myself getting hooked into the new lyrics, leaning, leaning in to hear what you were saying.

God you looked and sounded beautiful.

Dereck passed me a joint that someone else had passed to him.

“WHAT ALBUM IS THIS SONG FROM?” I shouted.

“THIS IS FROM 4:13 DREAM” he shouted back.

“IS THAT ABOUT TO COME OUT?” I shout-asked.

“NO,” he shouted “IT CAME OUT, LIKE, SIX MONTHS AGO.”

And it was then that I realized, without a doubt. It hit me and it hurt.

I abandoned you.

I was a Bad Fan.

Along with so much of the other music I listened to, I wandered out of the Church of Fandom in my early twenties and by the time I was in my mid-twenties The Dresden Dolls were in full touring mode. I was spending most of my waking life on the phone or on the computer, trying to make sense of this weird fucking life that I’d so wanted and I was so grateful to have – but at the same time, it destroyed something I cherished, which was the ability to hang out and absorb music, to live IN it.

I wasn’t a fan anymore. I couldn’t be. I was too busy working.

The magical mystery of needle hitting vinyl and sound suddenly appearing and the awe I felt when confronted with exotic, artistic beings on a screen or stage was replaced by the van, the stinking dressing rooms, the cables not working, the glare of the inner workings of tape and pro-tools, of booking and settling, of wheeling and dealing and moving and shaking.

At the end of the night, after the fans cleared out of our own shows and we climbed in the van, I always asked for the radio off please.

Music stopped being a ritual of joy and feeling and connection and turned into noise, into one more distraction. Piles of CDs always darkened my doorstep and I felt beholden to every band who thrust a demo tape, CD and (later) myspace link my way with a look of such yearning that i knew, i knew knew knew that owed it to this person to give some time to their music, because they were giving time to mine. On top of that, there was other noise all around. Tour noise, press noise, life noise, lawyers-and-managers-and-agents-talking-on-the-phone noise.

When the noise stopped, I didn’t WANT to fill it with music anymore. I wanted to fill it it with silence. Or talk radio.

I couldn’t go to live shows and not just see people working. It was so rare I’d see anything I liked. I sort of gave up, decided I’d gotten jaded. I stopped listening to you after Wish. I bought the albums (I could afford to now, I was on the up and up, throwing money around in record stores and leaving with stacks of new music that would then collect dust on my kitchen counter next to piles of free CDs that people would thrust at me at music conferences, CDs which were becoming a commodity as ephemeral and valueless as junk mail), but I couldn’t focus.

I could barely name one song you’ve written in the past seven years.

After watching you last night, I feel like I’ve done something terribly wrong.

You….

You helped saved me, you opened me up, helped me out of the darkness and gave me the tools to transmit myself, and I let you go.

Why did I do that?

I guess I had to…? To become….this?

To be a You for Other People? Maybe. I dunno.

I mostly feel like an asshole, a hypocrite, because I expect so much from my own fans.

I expect them to stay with me and love me forever and ever if they’ve loved me at all.

I expect them to follow through, to keep calling and checking in, to commit to the relationship.

But people, fans, friends, they do trail away, don’t they? Have children, have jobs, have schedules, forget about the songs they loved, maybe feel a little jolt of nostalgic happiness when they hear them on the radio but would never think of going to a live show….

You can step in the same river twice. You can never go back. Right?

Well. I went back and it worked. You made be remember. A lot of things.

As I stood there in the crowd at Coachella, I found myself wanting to dance. Dance like I used to in goth clubs, surrounded by dry ice and uninhibited by beer.

I felt self-conscious at first. But I just did it. I sang my fucking brains out and I starting dancing. And the more I sang, the more the people around me starting singing.

They knew the words, most of them.

I felt like I’d found my place, finally…not among the goths, not even among The Cure fans…but among the collected randoms, the flotsam and jetsam of coachella who were standing witness to you making music in that moment.

I held the hands of those standing next to me. I found myself taking Dereck’s hand. We screamed Cure lyrics gleefully in each other’s faces.

For a minute, we were best friends.

I never, ever would have done that ten years ago. I would have been scared shitless to do that when I was 23.

I’ve changed. I guess I’m brave now.

Was it the gin and tonics? I think they probably helped. But mostly, I think I understand something now that I didn’t back then.

These people, who didn’t need to wear the badge of black or goth (anymore, at least), these people who were not afraid to wear pink and sing at the tops of their lungs along with Cure songs, loud unabashed songs about BEING ALONE and FEELING AFRAID …

…it’s just….all of us.

I wish I’d understood this when I was in high school. I advertised my misery through my clothes. Little did I know that so many others were just as miserable and afraid but didn’t want to show it. I just assumed (as we all mostly did) that everyone was like me at some level, and if they weren’t making a point of looking sad and pissed off, well…fuck them, they didn’t understand. Many high school reunions have proved that theory WAY wrong.

I’ve heard rumors that you hate being called goth. Peter Murphy feels the same way.

Maybe we should start a club. The UnGoth.

Here are some photos from Coachella (mostly by Dereck) with my new pals.

I’m (ahem) in the black shirt.

On far right – in my garland – is Charlie Todd, who runs the amazing group improv everywhere in NYC…total coincidence, I met him in the crowd.

Hopefully we’ll make some art.

and with Dereck, my momentary soul mate…

So that’s my story, Robert Smith.

I plan to buy your new record and give a good, deep listen.

I’m sorry I left you, I want to thank you officially for changing my life….and I want to be a real fan again.

And if we never collide, just please know….I truly love what you do, what you are, and what you reminded me of the other night.

(Conversely, if you need a keyboard player….I’ll come for free, as long as you eat with me a couple times and we can share at least one bottle of wine and 3-5 stories each.)

Last but not least: have a very, very happy birthday.

I hope when i am 50 i am rocking as fucking hard as you, smiling so wide and still trying to change the world through being real and true for people…goth and UnGoth.

I love you.

Please never stop.

I won’t either.

With deep love,

Amanda (Fucking) Palmer

P.S. One last photo….i think this was during “Push”…Dereck capturing my ecstacy. That’s you, or some blobby shape of you, in the background. Once again, I swear that even though it looks like i am rolling HARD on ecstasy, there were no heavy drugs involved: